Upon his arrival at a Māori village in the lush North Island forests of Aotearoa New Zealand sometime in the late 1830s, Cornish missionary William Colenso noticed something curious. It was a momentous occasion—Colenso was reportedly the first European to visit the community—but he was distracted by a pot. According to his account, Māori women were cooking “potatoes” (possibly kumara, a sweet potato-like tuber) in a bronze pot over a hearth, rather than the more traditional method of placing heated stones in a wooden vessel. It was particularly odd because the village had not established trade with foreigners and therefore, thought Colenso, had no access to bronze, which was not manufactured on the island at the time.

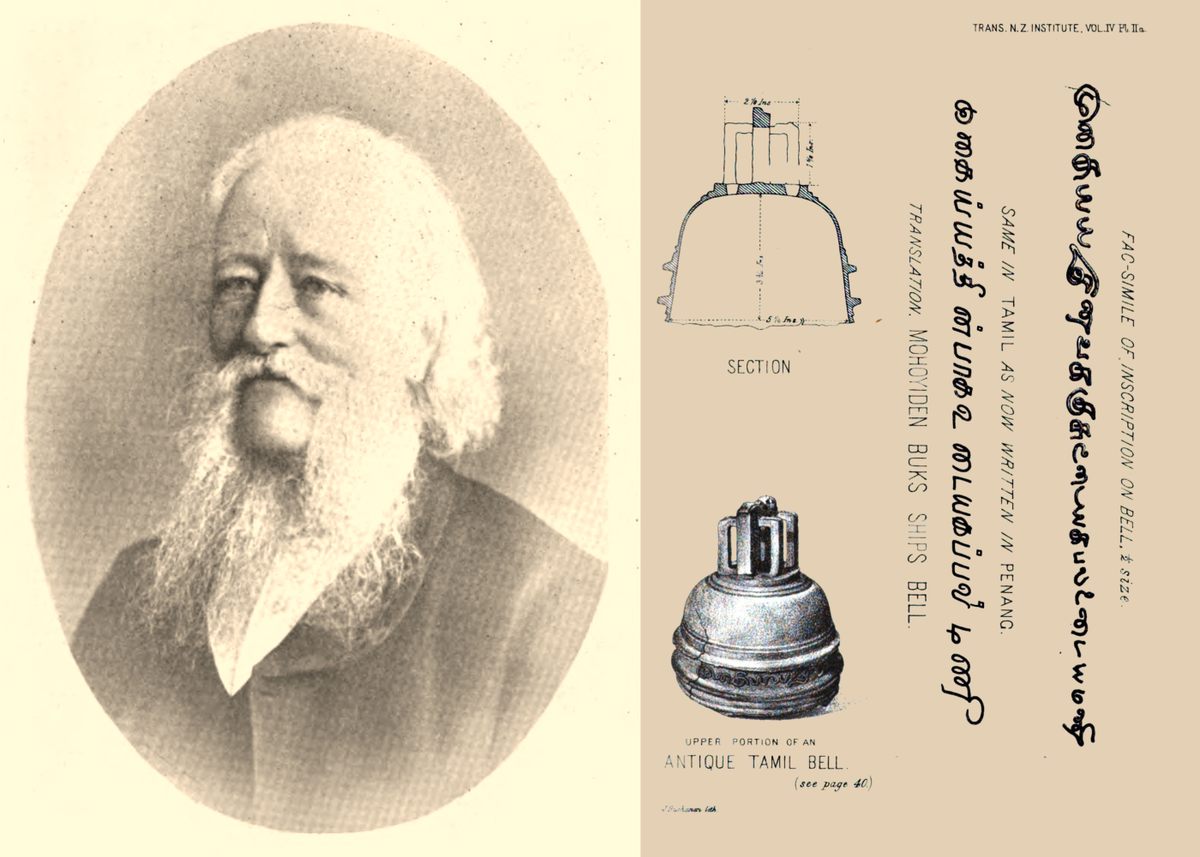

Colenso looked closer. It was a strange pot indeed. Roughly 6.5 inches high and 6 inches across, it had prominent ridges and an uneven lip, as if part of the pot had broken off. Embossed on the bronze were loops and swirls of a language that wasn’t English. This was no pot, Colenso realized. It was the top of a ship’s bell.

The Māori women told Colenso that it had been with them for generations: Their ancestors had found it in the roots of a tree that had toppled in a storm. Intrigued, Colenso traded the bell for a cast iron pot. When he died in 1899, the object was bequeathed to the Colonial Museum, which would later become the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, located in Wellington.

For more than a century, scholars puzzled over the object, known as the Tamil Bell for its embossed writing, which is in Tamil, a language spoken today in southeastern India, Sri Lanka, and Singapore. Almost everything else about the bell, including how it ended up in New Zealand, remained a mystery until Nalina Gopal, an inquisitive museum curator from Singapore’s Indian Heritage Centre, arrived in Wellington in 2019. Her tenacious detective work would reveal surprising details about the bell—and also raise new questions.

Touching the cold bronze of the Tamil bell for the first time ignited Gopal’s interest. “It was a surreal moment,” she says, her eyes lighting up at the memory. As with Colenso nearly two centuries earlier, Gopal was struck by the Tamil Bell’s incongruence. There are no historical records or archaeological evidence that Tamil seafarers ever sailed to or traded with New Zealand. Simply put, the bell defies explanation. “It’s like a UFO,” Gopal says.

The bell’s original swell is gone, and only the crown, not much larger than her cupped hands, remains. Its size raises questions about Colenso’s original story: Would it have been big enough for cooking potatoes? “Maybe baby potatoes,” Gopal says with a laugh.

Gopal dug into previous theories about the bell. As early as 1882, New Zealand scientist William Maskell believed that the bell might have been in the possession of some well-traveled sailor, who kept it as a souvenir from a South Asian port but lost it somehow on the North Island. In her 1996 book New Zealand Mysteries, historian Robyn Gosset suggested that a ghost ship—its crew having died or abandoned the vessel—might have drifted for thousands of miles before wrecking on New Zealand shores.

One thing people familiar with the Tamil Bell had agreed: It must be very old. It looked old, after all, and the script had been previously dated to the 14th or 15th century. Gopal, a native Tamil speaker from southern India, dismissed this conclusion immediately. “The older [Tamil] gets, the more difficult it is to read because it’s further removed from how the script is today,” Gopal says, adding that, when she saw the bell, “I could read the Tamil.” With the help of an archaeologist skilled in analyzing ancient scripts, Gopal discovered the bell was most likely made in the 17th or 18th century.

Next, she turned her attention to the meaning behind the inscription, which previously had been translated as “the bell of the ship of Mohideen Bux.” While the English spelling of the name was uncertain—it might have been Mohideen Baksh or Mohaideen Bakhsh—the consensus had been that the bell definitely belonged to a ship owned by Mohideen Bux. Gopal discovered otherwise.

“The bell’s inscription translation was quite literal,” she says. “And I don’t think they did much research into who or what Mohideen Bux might be.”

As she scoured books for more information, she came across the work of J. Raja Mohamad, a researcher based in Tamil Nadu and a former curator at a regional museum there. Mohamad had been trying to solve the bell’s mystery since the 1980s.

Mohamad had been the first to suggest that Mohideen Bux might not have been the owner of the ship, but the name of the ship itself. Gopal and Mohamad combined forces to learn more. Mohamad pored over maritime archives from Tamil Nadu, while Gopal combed through documents at the National Archives of Singapore. The shipping records are analog, requiring hours of painstaking searches. Their careful work led to an unexpected find.

“A lot of Muslim merchant communities in Southeast Asia revered [a saint called] Mohideen Bux,” says Gopal. Mohideen Bux, she and Mohamad learned, was a common name for ships sailing from Tamil Nadu. “The idea was that the ship would be protected because it was named after the saint,” Gopal says.

She saw the Tamil Bell’s inscription, Mohideen Bux udiya kappal udiya mani, in a new light. “Udiya means ‘belonging to someone,’” says Gopal. “Perhaps in this instance what they actually meant is that the ship was under the care of the saint, rather than that it belonged to a person.”

Gopal and Mohamad were less successful connecting any Tamil ships to New Zealand. They found no evidence of any lost trade networks, nor could they pinpoint which ship might have carried the Tamil Bell. According to Mohamad, after a story about the bell in 1975 made a local media splash, several families in the region had laid claim to it. Three families believed they were descended from sea traders who might have once owned a ship by that name. One family had even petitioned Te Papa museum to return the bell to Tamil Nadu, where they believed it belonged.

When Gopal returned to Singapore, she took the bell with her, on a loan to the Indian Heritage Centre. For the seven months it was on display before returning to Te Papa, Gopal says it drew Tamil Muslims excited to see this fragment of their past.

Ultimately, Gopal thinks the bell should stay in New Zealand. “It’s part of the bell’s journey,” she says. Perhaps, she adds, the bell can do as it has apparently always done: move around, visiting different museums the way the ship carrying it once pulled into far-flung ports.

For now, the bell rests in Te Papa, still wearing its mantle of mystery. And, perhaps, the faintest patina of charcoal from a cooking fire.