In February, in our family iMessage group, my brother asked our mother to indulge his craving for egg salad sandwiches. “That is so weird,” I replied. “I dreamt of mom’s egg salad two days ago.” It had been years since I had eaten it, but chewing in my dream, I realized the crunch of the celery that my mother added was the secret. “I had the same epiphany!!!” Dustin texted back. “The celery!!!”

He went on: Maybe this was the chemo he was doing, but Chinese and BBQ from spots we liked out of state were also appealing. He beat—by half a second—a message I was in the midst of sending about how I longed for food from those exact places. We exclaimed at the chances. Dustin joked that my two-month-old had “given us magical powers,” or that our family dog was controlling our minds. “THE LIMIT DOES NOT EXIST,” he said.

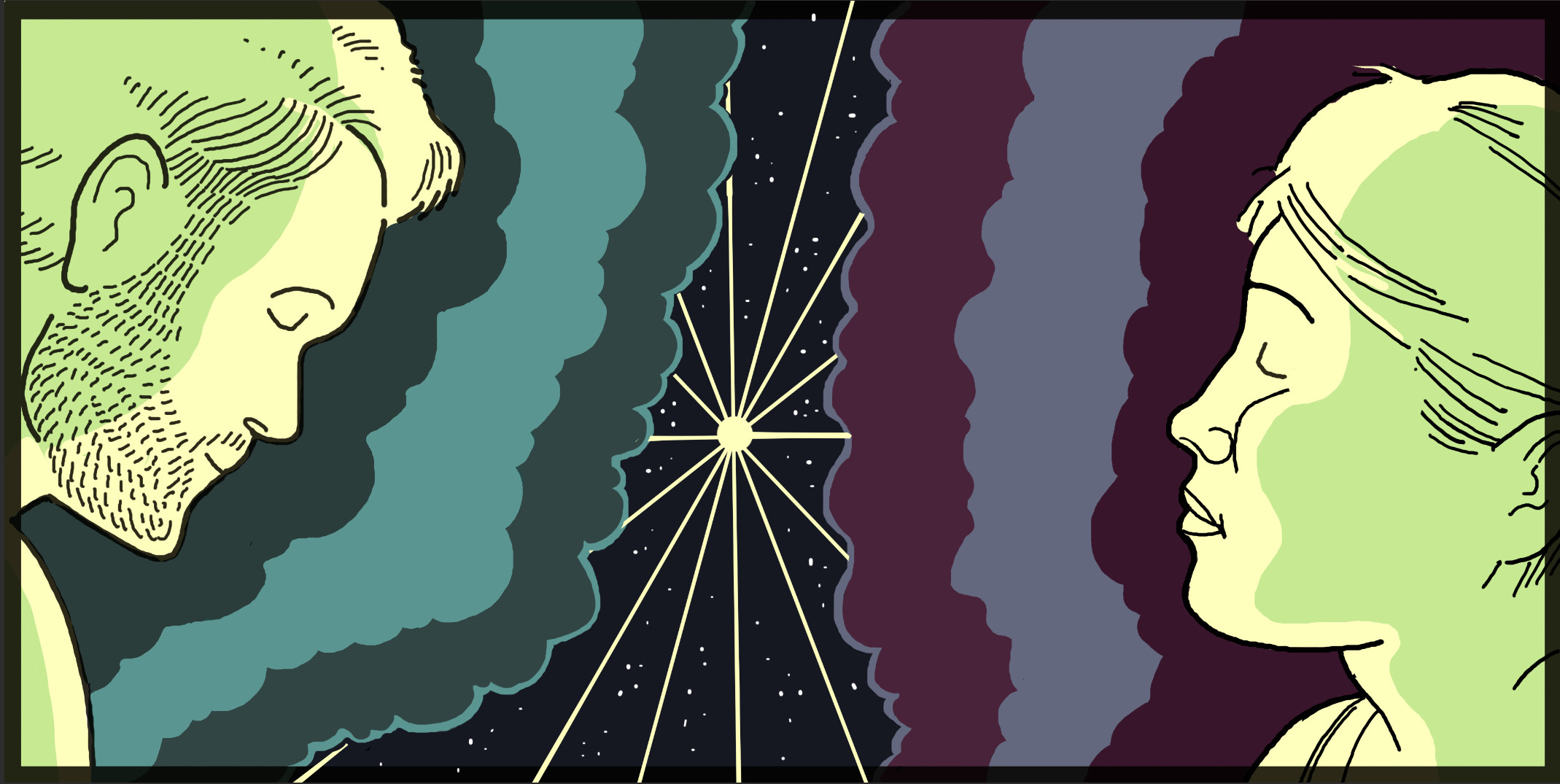

When my brother passed away at twenty-nine from complications of leukemia some weeks later, I livestreamed his funeral in Florida from under lockdown in France. The distance between us was imponderable, as great as it could ever be. We’d both wanted the egg salad. That the connection between us would be cut did not follow. Grief breaks your heart; also, it breaks your brain. While we keep the people we love in our hearts, it began to seem that Dustin was in my head more than anywhere else.

Mark Twain, though he did not go for spiritualism or immortality, would have agreed that siblings could tune into each other from opposite sides of the ocean. He believed, he once wrote, that a mind “still inhabiting the flesh” could reach another mind at great remove. There was an inciting incident in the spring of 1875 (before Twain’s red hair went gray), which he recollected as “the oddest thing that ever happened to me.”

The mail had just come at Twain’s home in Hartford, and he held a fat letter, still sealed. “Now I will do a miracle,” he drawled. He recognized the hand of someone from whom he said he hadn’t heard in eleven years. Even so, he knew without opening it that the letter contained a book idea. Their minds had been “in close and crystal-clear communication with each other across three thousand miles of mountain and desert on the morning of the 2nd of March.” Twain, in effect, had sat down to write to this very contact, on the same day, about this very same idea. Twain answered: “Dear Dan—Wonders never will cease.”

Dan De Quille was the alias of William Wright. In 1862, both men had started as staffers at the Territorial Enterprise in Virginia City, Nevada, and fast became a double-barreled force: the best writers at the hottest paper during the Silver Rush. De Quille was six years older than Samuel Clemens, who showed up, dusty, at twenty-six, as “Josh,” one of dozens of pseudonyms he tried on before becoming Twain.

The territory was given to gunplay, dustups, fire, pranks, and “high hope,” as Twain wrote in Roughing It, and its print culture was unruly, too. “Get your facts first, and … then you can distort ’em as much as you please” was his twenty-four-year-old editor in chief’s guidance. Twain, De Quille said, was averse to fact-heavy “‘cast-iron’ items,” but he was ace among the journalists there who played hell with objectivity and spun elaborate “sells,” from lampoons to hoaxes. (De Quille favored science hoaxes.) The boomtown’s denizens, Twain biographer Gary Scharnhorst points out, had an appetite for Harper’s, The Atlantic, Dickens, and Shakespeare, as well as for the infotainment. It was said the Enterprise’s owners carried home thousand-dollar daily profits in water buckets.

De Quille and Twain “often cruised in company.” They shared a desk. They shared lodging—a double bed. “Mark and I agreed well as room-mates,” De Quille recalled. “Both wanted to read and smoke about the same length of time after getting into bed, and when one got hungry and got up to go down town for oysters the other also became hungry and turned out.” (Scharnhorst told me the theory the two were lovers has been “roundly scorned” by scholars, especially by Larry Berkove, the late authority on these journalist-humorists.) They enrolled in fencing club. “It is said to be highly amusing to witness a set-to between these two ‘roosters,’ they sometimes get so terribly in earnest,” reported the Gold Hill Daily News, which often trafficked in their antics. “Dan De Quille and Mark Twain are to be married shortly,” the paper kidded in April 1864. However, the next month, Twain hotfooted it to San Francisco. The bromance had lasted less than two years. “Nevertheless, their association was more intense and long-lasting than has been appreciated, for their sharing of ideas and stories must have been so extensive as to constitute a common pool,” Berkove reflected. He was unsurprised “that minds which were once so familiar and in tune with each other should continue to produce, even after the interval of many years, thoughts and compositions which bear the impress of the former partner.”

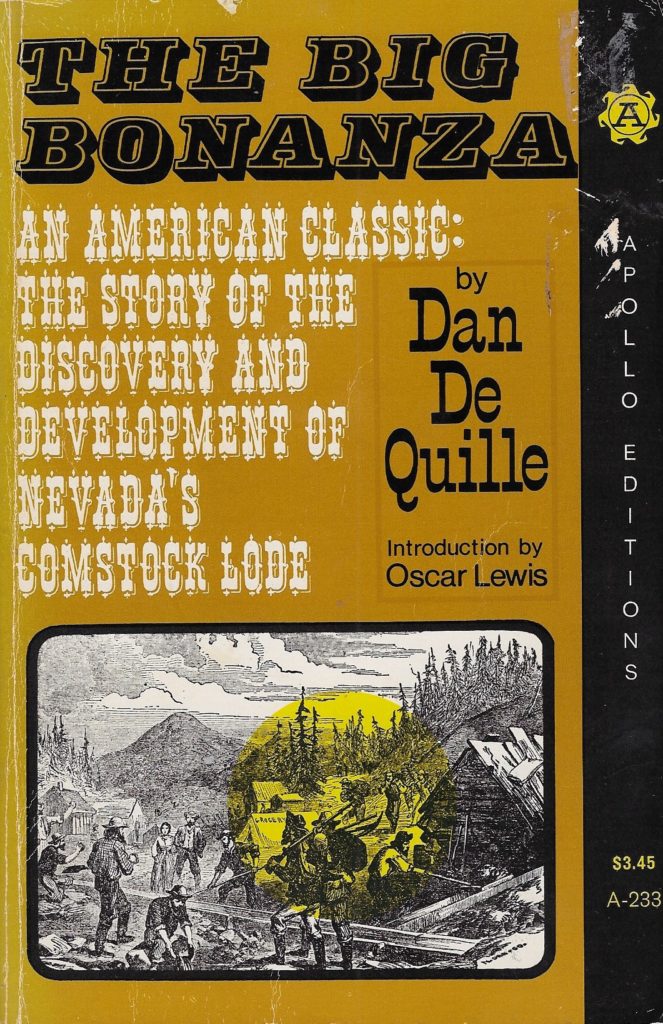

Ten years later, in October 1874, the motherlode was unearthed in Virginia City. The vein, which De Quille called the Big Bonanza, was the richest silver strike in American history and would pay out north of a billion dollars in bullion. De Quille was then the Enterprise’s mining expert (“with a love for the lode”) and a group of the mining magnates wished him to chronicle their Silverado. De Quille, a dipsomaniac who labored crazy hours for moderate moola, had other manuscripts on the stove, but he resolved to ask his former friend, the now-famous Twain, for advice on how to “turn clown.”

And, eureka! As De Quille was writing to him, Twain was reckoning that “the market was ready” for “The Story of the Comstock Lode, with all the strange & romantic fortunes & incidents connected with it,” and the person to pull off such a history, obviously, was “dandy quill.” Twain outlined the book he envisioned, hooked De Quille up with his publisher, and welcomed him to Hartford to “grind literature all day long in the same room,” blued by cigar smoke.

The Big Bonanza (1876) is still the definitive, if inchoate, history of Nevada’s Comstock Lode and the frontier’s bonanza camps.

In 1878, Twain wrote about mental telegraphy in A Tramp Abroad. And before going to press, he blotted all of it out. “I feared the public would treat the thing as a joke and throw it aside,” he said, “whereas I was in earnest.” About a decade later: “I tried to creep in under shelter of an authority grave enough to protect the article from ridicule—the North American Review.” The chief, Lorettus Metcalf, insisted on Twain’s byline, but Twain understood that his forked tongue had saddled him with a believability problem, and people would not take him seriously, dammit. “So I pigeonholed the Ms., because I could not get it published anonymously.” Finally, for Harper’s, sixteen years after he received De Quille’s letter, in December 1891, Twain trotted out his surety that egg salad incidents like ours were not accidents.

“That is the puzzling part of it,” he wrote in “Mental telegraphy. A manuscript with a history.” “We are always talking about letters ‘crossing’ each other, for that is one of the very commonest accidents of this life. We call it ‘accident,’ but perhaps we misname it.” Elsewhere, Twain had proposed the “rapport between two minds” operated on “a finer and subtler form of electricity,” which inventors must harness for a thought-sending device, called the “phrenophone.” We’d be able to say, “‘Connect me with the brain of the chief of police at Peking.’”

A few years later, Twain returned to the subject of mental telegraphy in Harper’s with a fresh roll of examples. They were intricate. One day, for instance, he and his friend Joseph Twichell were going to visit Twichell’s daughter—to whom Twain was like an uncle—at her boarding school. As they journeyed, Twain told Twitchell of an encounter a while back: He was in Milan, when a soldier on leave approached him. Lieutenant H. explained that they’d met when he was a cadet and Twain and Twitchell had come to West Point. The soldier mentioned that he’d recently misplaced his letter of credit, and that an American couple with daughters—strangers—had lent him the money to settle his hotel bill. He was headed to repay them, and Twain went along. “I was introduced to the parents and the young ladies; then we separated, and I never saw him or them any m—.” Twain was interrupted as the trolley arrived at their stop. At Miss Porter’s School, lasses streamed by. A girl came up and shook Twichell’s hand—she was, she explained, a friend of his daughter. Then she turned to Twain: “And I wish to shake hands with you too, Mr. Clemens. You don’t remember me, but you were introduced to me in the arcade in Milan two years and a half ago by Lieutenant H.”

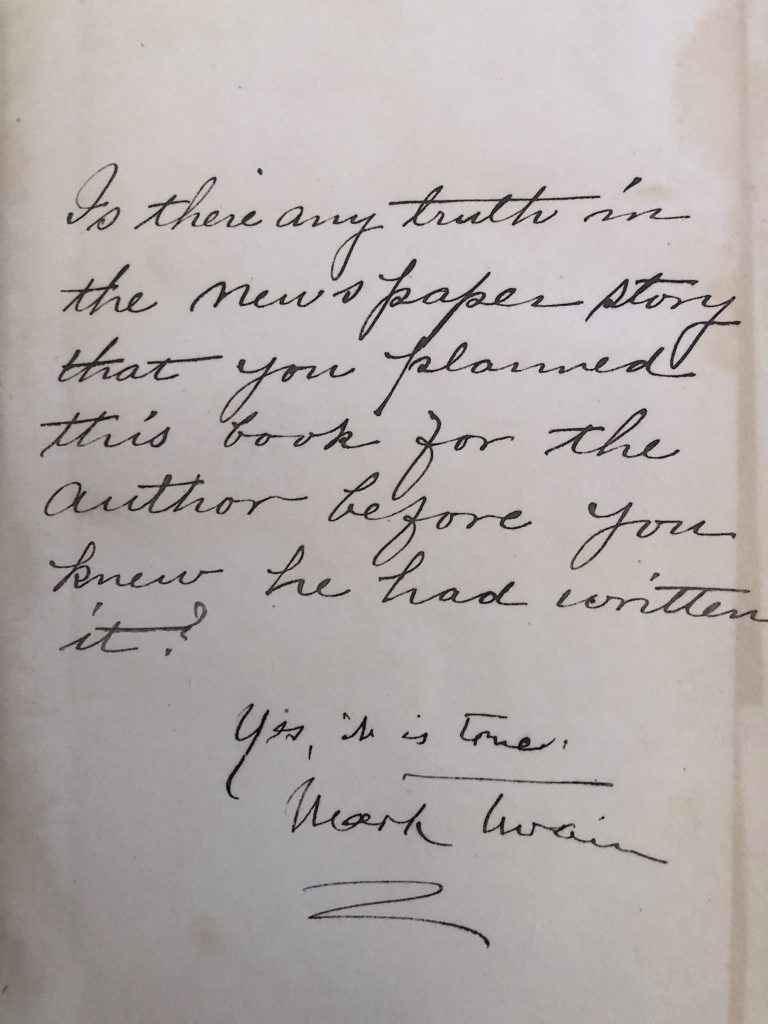

The end page in a copy of The Big Bonanza. Its original owner sent the book to Twain with the question, “Is there any truth in the newspaper story that you planned this book for the author before you knew he had written it?” Twain returned the book with an answer. “Yes, it is true.” Courtesy of Kevin Mac Donnell, Austin, Texas.

“I don’t exactly know what to do with Twain’s psychic claims,” Scharnhorst responded, when I asked him if Twain’s notion of mental telegraphy was another leg-pull, the same brand of jest he undertook in the West. “I don’t think it was.”

“But it’s basically coincidence,” Kevin Mac Donnell, a rare book dealer and Mark Twain scholar who owns the largest private collection of Twain material, including nine thousand first editions, letters, and manuscripts, told me by phone. “Twain dispatched fifty thousand letters in his lifetime, easily, and was a social butterfly, ever traveling. Of course his letters crossed and he ran into people in the street.”

Some of the Bonanza business as Twain narrated it does not prove out. A copy of the letter Twain sent in reply to De Quille’s letter survives. His dates are off. He tells De Quille his wife, Livy, was there when the mail came; in the magazine piece, Twain’s witness is another relative. Those are peccadillos. Less so the pretense that he “had not seen and had hardly thought of [De Quille] for eleven years” and did not even know if De Quille was alive. “That’s fudged,” said Mac Donnell. “He knew how to create buzz; how to quicken plot.” In March 1869, Twain wrote to De Quille that he intended to marry. Afterward, Twain sent a wedding announcement personalized with ancient in-jokes: “Old Dan, my abused roommate—{but who stole old Mrs. Fitch’s pies, nevertheless—& Daggett’s wood.}”

Still, ben trovato exaggeration does not contradict sincerity. “As a mental exercise, as a literary device,” Mac Donnell said, “you can see how mental telegraphy works for Twain and connects to his overall open-mindedness.” Mac Donnell referred to Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc, Twain’s last novel. “He doesn’t question her visions,” Mac Donnell said.

In 1882, the Society for Psychical Research formed in London to investigate paranormal human experiences “without prejudice or prepossession.” The society did, however, want to prove thought transference, and that year one of its members coined the term “telepathy.” When Twain joined two years later, he told SPR’s cofounder that, ever since Bonanza, he had known the tête-à-têtes were real. When the notion to contact someone hit him, Twain confessed to feeling “like a mere amanuensis.” He assumed the other person had just cabled him. For the rest of his life, Twain continued to note the freakiness of telepathy.

Three years before his heart attack, in 1907, he wrote that “inventions, ideas, phrases, paragraphs, chapters, and even entire books” could all flow brain to brain. He said, resigned, “I often originate ideas in my mind but get almost all of them out of somebody else’s.” The inevitability of unintentional plagiarism bothered him. In November of 1907, Twain heard about a new story by George Bernard Shaw. It echoed in both style and substance one he’d composed seventeen years earlier—“hilarious and extravagant to the verge of impropriety,” and unread by anyone, because Livy would not let it print. Twain concluded that “Mr. Shaw must have gotten those incidents out of my head…”

Twain was serious, and not way off. He anticipated brain–computer interface, for one thing. Last fall, the system dubbed BrainNet—a kind of phrenophone—allowed three people in different rooms to play a game of Tetris together with their minds. “I’m telling you about something so sci-fi,” Chantel Prat, one of the neuroscientists who developed BrainNet, said on a call. BrainNet uses a machine to decode brain activity from a sender brain, an electroencephalography (EEG) cap to record that activity, and computer software to translate it for a receiver brain. “It’s very much like a microphone,” Prat explained. “This electrode sits on the scalp and picks up the electrical activity that’s happening inside the head. The signal extends outside the head. We can—we do—record outside the head what’s happening on the inside of it.” I asked how far brainwaves can travel: Were we talking centimeters? Inches, feet—football fields? Prat could not say. But it was not across mountains, deserts, or oceans.

“Most of our thoughts transmit at 40-200 hertz. They can’t go very far,” she said. “But the brain is like a radio. Brainwaves come in different frequencies; some happen at 2-7 hertz, and those lower frequencies have a farther range.” Researchers studying neurosemantics at Carnegie Mellon are able to decode words and even sentences in our brainwaves, but Prat wanted to emphasize that we can decode much more than we can encode. “When we put info in the brain,” she said, “it’s a lot like a sledgehammer coming down: We cannot put an idea in the brain. We can make somebody’s finger twitch.” She appreciated Mark Twain’s cast of mind, though.

In a socially distanced world, disconnected from Dustin, I’m left remembering his capacious imagination for human contact. People get into our heads. And when we know they are out there, thinking of us, us thinking of them, that signal is so clear. What Twain told De Quille is true: “human sympathies can stretch.”

Chantel Tattoli is a freelance journalist. She’s contributed to The New York Times Magazine, VanityFair.com, the Los Angeles Review of Books, and Orion and is at work on a cultural biography of Copenhagen’s statue of the Little Mermaid.