In the early months of 2020, I stumbled upon a YouTube channel called Modern Chinese Cultural Studies, run by literary and cultural historian Christopher Rea. I had developed a recent interest in Chinese silent movies and was delighted to find this YouTube channel chock full of such movies. Some I’d seen, others I’d only read about—all accompanied by newly translated English subtitles that were often quite different from subtitles I’d previously seen on the market.

Over the next year, Rea—a professor of Chinese at the University of British Columbia—and his team continued to upload Chinese films from the 1920s-40s (including sound pictures), and it was during this time that I discovered the YouTube channel was actually part of a much larger project. In addition to providing improved subtitles for the films, Rea was building out a (still-growing) website and a free online film course. A plethora of information, free to access for anyone interested in early Chinese film history.

It was also around this time that I learned the project had begun with Rea’s latest book, Chinese Film Classics, 1922-1949, now available from Columbia University Press. Our Culture reached out to Rea to discuss the book, the YouTube channel, the difficulties of properly translating Chinese films, and what he hopes to achieve in the long run.

In starting off, could you tell us about your interest in Chinese film began? How did your interest lead to the book Chinese Film Classics, 1922-1949?

I’ve been interested in Chinese films since high school. I was a Chinese Language and Literature major in college, and continued doing Chinese literary studies in graduate school. I watched a few 5th generation Chinese films of the 1980s and ‘90s during that time, and found them fascinating. As for this particular book project: I’d written a book about the history of laughter and humor in China in the early 20th century, The Age of Irreverence (2015). Laughter is not strictly a literary thing—it spans forms and genres—so I watched a lot of films, too. I liked a lot of the films I saw and became interested in doing a project on them.

Your book covers fourteen Chinese films made in the years 1922-1949. How did you choose the films, and why did you choose that particular set of dates?

There have been a lot of chronological histories of film in China—from the early days to the present—but I really wanted to focus on films as texts and treat each film fully. If you include more chapters and cover more films, either you’re going to end up with an enormous encyclopedia, or you’ll give short shrift to each film. So, I tried to strike a balance.

There are only so many early Chinese films that 1) survived the fires of war, and 2) have been released from the archives. The date 1922 was set by availability: the earliest complete Chinese film that is fully available, Laborer’s Love, is from 1922. As for 1949, that was an obvious point to stop, because the new Communist government set in motion huge shifts in cultural policies at that time. These changes (which took several years to implement) impacted not only filmmakers but studios, which had been private and were suddenly nationalized. Virtually all filmmaking became subject to top-down government directives, culminating in a major re-org in 1952.

I chose my favorites from what’s available and devoted each chapter to a particular film. I talk about how the films relate to Hollywood cinemas and to European cinemas—and what was going on in China at the time, including efforts to articulate an indigenous cinematic style. Each chapter tries to understand the film 1) as a work of art, and 2) within the historical context of its production and reception. The book is very much a starting point for people interested in Chinese film history.

How did the book project lead to the YouTube channel? Also, some of the films you’ve subtitled have already been given subtitled DVD releases. Why did you choose to re-subtitle them?

I’d been teaching Chinese films for about a decade and had been constantly frustrated by the poor quality subtitles on the market. A couple of private companies distributed these films in North America, but the subtitles were uniformly bad—inaccurate or incomplete. They would translate dialogue but not text onscreen—so if there was a shop sign, you wouldn’t know what it says. I’d been waiting in vain since graduate school for someone to properly translate these films. Eventually, I decided just to do it myself.

I translated all the films discussed in the book (with the exception of New Women [1935], translated by Eileen Cheng-yin Chow) and made them available on the channel, which I was able to do because the underlying rights for the films are out of copyright. (Some archives retain copyright over particular copies or restored versions, which I can only use with permission.) I had started the Modern Chinese Cultural Studies YouTube channel in 2017, mostly for uploading videos of UBC research on China. It wasn’t until around 2020 that I started updating it in earnest with full films, film clips, and video lectures.

I have now created a Chinese Film Classics website, which contains all of the translated films; a complete, semester-long open-access course with 22 video lectures; and additional resources. So, I suggest that anyone interested in early Chinese film history start there.

Similar question: some of the silent films you’ve translated were originally released with bilingual intertitles—with Chinese on the top and English on the bottom. Why did you choose to re-translate films that were originally released with their own English translations?

What I discovered about the Chinese-English intertitles was that they are also inaccurate/incomplete, or they use archaic English. Also, there was no standardized rendering of Chinese names back then. Filmmakers weren’t using the Wade-Giles romanization system, and stars were often given different English names—so if you only read English, you don’t know who they’re talking about. Who is “Lily Yuen”? Oh, it’s famous actress Ruan Lingyu. Who is “C.Y. Sun”? Oh, it’s leading director Sun Yu. In translating the intertitles, I include pinyin [the current standard romanization system for Chinese characters] for names and point out differences between the Chinese and the English text. Representing such differences creates a unique copy of the film.

It’s fascinating to me that bilingual intertitling of Chinese silent films dies out after a certain point. Silent films of the mid-1930s tend to feature Chinese intertitles only, indicating they weren’t made for a bilingual market to the same degree.

What are some of the difficulties of translating Chinese to English? Is translation a matter of simply matching words, or is it more complicated?

I think it would be interesting to cut loose Google Translate on one of these films and see what results. Language changes over time, spoken speech versus written speech changes. So, there’s rather archaic-sounding Chinese in the films that doesn’t sound like 21st century Chinese. You also have slang, instances of classical Chinese, instances of dialect that don’t make sense. It’s really quite a mix, and that’s part of the fun—and the challenge—in translating these films. You have to be familiar with the idiom of that time period.

For example, when a character in Long Live the Missus! (1947) says, “Such-and-such a film is playing at the Mei qi,” viewers will wonder: ‘What’s the Mei qi?’ If you translate it phonetically, viewers will have no clue. You have to know they’re referring to a certain Shanghai cinema of yesteryear—the Majestic. So, there’s historical research involved, and I spent a lot of time reading 1920s-40s Chinese magazines and newspaper advertisements.

Another challenge is that some of the films show signs of censorship. Sometimes the editing seems to have left something out. And this raises interesting questions about what was preserved and what wasn’t—and when. What was changed in the Republican era in the 1920s-40s [by government censors, or by filmmakers themselves], and what was changed by the China Film Archive when they released the films in the 1980s and ‘90s?

Since you mentioned dialect, did dialects make translating the sound films difficult in any way?

You did have regional language markets back then—Cantonese markets, for instance—but it wasn’t a huge factor with these Shanghai films. Some of the major studios, like United Photoplay Services (Lianhua), were closely tied to the Nationalist government and supported efforts to promote guoyu, a national spoken language. So they trained actors to speak a certain way—with mixed success. In certain instances, the dialogue is very slow and halting.

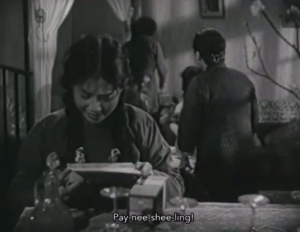

Now, there are dialect jokes. In Crows and Sparrows (1949), there’s a Shanghainese dialect joke about the pronunciation of the word pay-nee-shee-ling (“penicillin”). A character remarks that in Shanghainese, “penicillin” it sounds like “dead man coming up.” That’s a clear dialect joke.

The main difficulty is often the poor quality of the sound recording. Sometimes the dialogue is hard to comprehend and you can hear the whir of the camera in the background. We’re currently translating a film from the 1930s which has very poor sound. First you need a Chinese transcription of the dialogue, then you need to translate it, then double-check everything. In some cases, Chinese scholars have compiled the complete works of directors like Zheng Junli, including all of the screenplays. But the screenplay and the actual film do not always match. So you can’t rely solely on the screenplay for translating. All of my translations are based on the film itself.

When I watched your subtitled copy of Sports Queen (1934), I noticed that you rendered instances of scatological humor that were missing in the subtitles for Cinema Epoch’s DVD of the same film. Was preserving nuances such as these another intention in translating?

I’m very much about preserving the integrity of the text. So when the original Chinese says chu gong (“take a dump”), I’m going to translate that. As you mentioned, the subtitles on the Cinema Epoch Sports Queen DVD completely cut that out—I’m presuming for prudish reasons. I feel that if it’s there, we should translate it and then we can debate whether we like it or not. If you silently omit anything, I think you’re doing a disservice to the text and the viewer.

In Sports Queen, there are also instances where they try to represent funny sounds in the intertitles. There’s a scene where a westernized young man trying to woo the future sports queen, and he calls her mee-ssu (misi, in pinyin), which the intertitle shows using the characters for “secret shit,” because this is how another character mishears the phrase. But what the speaker means is its homophone, “miss.” So I came up with a way to render the character’s silly over-pronunciation of a western term and preserve the scatological joke.

What is the future of the YouTube channel? What do you hope to accomplish?

There are new films being translated now—some by me, some by other people. I’ve recruited translators from Cambridge, Harvard, universities in Australia, even a high school student on the east coast in the U.S., who is translating two silent martial arts films from the 1920s. I’ve also worked with a couple of my research assistants at UBC: PhD students like Liu Yuqing and Yao Jiaqi, who helped with creating subtitles based on my translations and who worked with me on multiple rounds of revisions for every film.

Translating these films has been labor-intensive. I’ve been doing this nights and weekends for quite a while, but the results have been gratifying. I’ve heard from colleagues across the world, from people who do scoring for silent films. I’ve been contacted by someone who said, “My grandfather was a producer for three of the films on your channel, and I’ve known very little about him. I don’t know Chinese, but now I can appreciate his work through watching these films.”

I’ve also gotten comments on the YouTube videos that have influenced my work. One director of a Chinese music ensemble in the U.S. Midwest pointed out that I was not often including credits for the composers in the YouTube video descriptions. I’d go back to the credits I translated and add those to the descriptions. He also did some research on his own and posted what he found in the YouTube comments. Beyond film history, I hope that this project inspires people to do other open access projects, in whatever field they’re in.

I also hope to enable more dialogue with people who don’t focus on Asian cinema but are experts in other world cinemas. Maybe they haven’t seen Chinese silent movies, but now they can compare and point out things to Asianists. “Hey, you should really check out that Fatty Arbuckle film or that Greta Garbo film, because there’s a resonance here.” This is really a project for educators, students, and the general public.

Lastly, any upcoming events tied to the book?

I will be doing public virtual events in the coming months, including an event on Laborer’s Love (1922) and two events at New York’s China Institute in July, which should be announced soon. I’ll be putting announcements on the YouTube channel, so people who are interested can check for news in the Community section.

But, again, the best place to get acquainted with the overarching project is the Chinese Film Classics website.

Our Culture would like to thank Christopher Rea for this insightful and informative interview. We ask our readers to check out the work that Rea and his colleagues have so ardently pursued.