There are many medieval villages in England that have disappeared throughout the years. However, one that remains more visible than most is the village of Gainsthorpe in Lincolnshire. When viewed from above, many elements of the village remain visible, such as the houses, barns and streets through earthworks in an unploughed field. Furthermore, Gainsthorpe was no small hamlet but a significant village, which can be traced from its earliest origins right through to its disappearance in the 17th century.

The Origins of Gainsthorpe

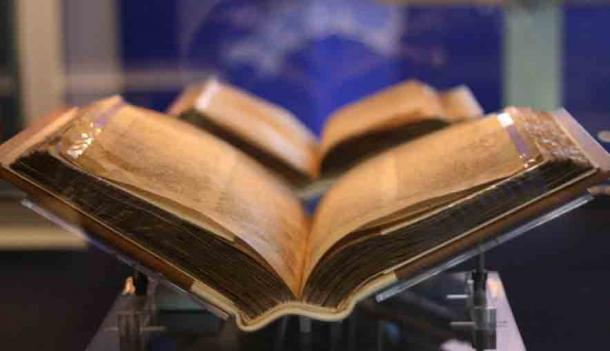

One of the earliest mentions of the village of Gainsthorpe is in the Domesday Book of 1086. This book was a great survey of England ordered by William the Conqueror after his conquest of the Anglo-Saxons. It sought to record how the land was occupied, by what sort of man and what stock was upon the land. The Domesday book shows how much dues and taxes should be due to the King each year. It is here where Gainsthorpe has its first mention, as the village known as “Gamelstorp”.

It was originally owned in 1066 by a Saxon lord called Ulgar or Wulfgar. This name is associated with 21 other places in the Domesday book, though it should be noted that these may not all be the same person. By 1086, though, the possession of the land had been transferred to a Norman lord, Ivo Tallboys or Taillebois. This perhaps implies that during the taming of England by William, Ulgar/Wulfgar was killed.

The original Great Domesday and Little Domesday books, National Archives, Kew, England (Andrew Barclay / CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 )

What is important to note is that Ivo Taillebois was an important Norman nobleman in the reign of William the Conqueror, and his successor King William Rufus. He was in command of the Norman army at the siege of Ely in 1071, against English resistance. As a successful Norman lord, Ivo seems to have had his principal powerbase in Lincolnshire, whilst also gaining extensive lands throughout England. This may suggest that Gainsthrope was a reasonably thriving village as far back as 11th century England.

In 1208, Gameslestorp was again listed in a royal document detailing a list of legal land tenure agreements, the extent of which shows that the village had continued to grow. There was a minimum of 19 fields covering 108 acres described in the document, as well as a chapel, a windmill and a bridge.

Life in the Village

The manor building in the village was unlikely to have been very grand, despite it being where the wealthiest and most prosperous people of the village would have lived. It had a separate barn for livestock and was mostly constructed of timber in an A-frame construction. This would have been accompanied by a single longitudinal roof beam with walls made of woven branches/reeds combined with mud in the traditional method. Reeds would have been in plentiful supply thanks to the floodplains surrounding the village.

The village people themselves would likely have been of the lower class of citizen, principally laborers and farmers with few people who actually owned their own land. Essentially, they were “serfs” (indentured agricultural workers) who worked the land for the local lord.

<iframe width=”917″ height=”516″ src=” https://www.youtube.com/embed/8L8n2o0KPJk” title=”YouTube video player” frameborder=”0″ allow=”accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture” allowfullscreen></iframe>

Whilst the cause of decline of the village is unknown, the population of the village was potentially badly affected by the Black Death plague that ravaged England in the mid-14th century. The last mention we have of Gainsthorpe is in 1616 when the Duchy of Cornwall noted in a survey that “neither tofte, tenement or cottage” was left standing. In 1697, Abraham de la Pryme visited the site of Gainsthorpe in which he recorded the ruins of around 200 buildings. It is some of this that can still be seen today.

The Ruins Today

Much of the deserted village survives today as earthworks in grassed fields, through raised ridges and sunken hollows. From an aerial point of view, there are three/four roads visible as a hollow way through earthen banks on either side of a sunken track.

Nothing remains of the village but impressions on the landscape (Simon Tomson / CC BY-SA 2.0 )

There are the remains of about 25 buildings that can be seen laid out across 15 enclosures. Each enclosure is likely to have been occupied by a family or workers. There is a mixture of smaller buildings, which were houses, compared to the larger buildings which were likely barns. There are also faint traces of ridges in the North that suggest that the village also had open communal farms lying beyond the private enclosures.

Fascinatingly there are also quarry pits potentially dating from the 16th or 17th century that seem to respect the boundaries of these enclosures. This implies that the village may still have been occupied by at least a select few as late as these dates. There also exists an early 19th century farm, that perhaps suggests that the Gainsthorpe was never truly deserted.

So What Happened?

Whilst it will be impossible to make a definite cause on the disappearance of the village, there are some theories that can help explain why it experienced a decline. As previously mentioned, the Black Death of the 14th century may have been a significant issue for the town. The Black Death was a plague that swept across Europe and Asia in the 14th century. Arriving on boats, sailors and traded goods spread the disease far and wide causing the deaths of up to a third of the population, maybe as much as 25 million people across the world. Large parts of the population in England subsequently died. It is possible that this destabilized the village life in Gainsthorpe.

The Black Death devastated the population of Europe (Moynet / CC BY 4.0 )

Equally, as the archaeology shows, industry became much more popular throughout the 16th and 17th centuries and there was a shift from rural living to urban living. Gainsthorpe itself is situated near large cities that experienced rapid population growth in the age of industrialization, such as Leeds, Sheffield, Lincoln, and Scunthorpe. It may have just been that people moved away from the rural village in order to seek a living in the big bustling cities.

Lost to Time

The village itself can still be seen and reconstructed through the earthworks and ruins that remain. Whilst the village started with such a strong background and grew to a reasonable size, it unfortunately became victim, like many other medieval villages of England, to plague, pestilence and industrialization.

Top Image: How could an entire village disappear? Source: Ivan Kmit / Adobe Stock.

By Kurt Readman