People are shopping like nobody’s business,” marvels Sherri McMullen. As the owner of McMullen, the buzzy Oakland, California, boutique, she would know. Her clients, she says, “are redoing their entire wardrobes.” Refrains she’s heard lately: “‘I don’t want anything in my closet’; ‘I want to redo everything’; ‘Everything’s too dark.’” (Bright colors and prints, she notes, are stepping in to fill the void.) “Whatever they were experiencing last year,” she says of her customers, “they want to feel the opposite way. Comfort dressing isn’t a big part of it.”

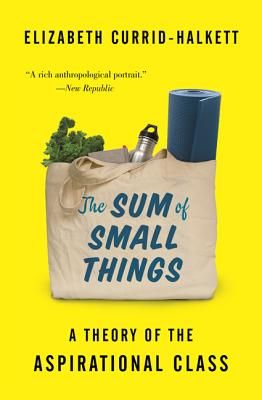

Can you blame them? Lockdown has driven a spate of “revenge shopping,” a phenomenon that was first observed in China following the end of quarantine and has now spread across a world reeling from the losses of the pandemic. Customers are making up for lost time, lost events, lost flaunting-it opportunities. Shopping, usually a joyous activity, is driven here by a kind of mania, and perhaps even grief. People are “seeking some experience or outlet that feels frivolous, because life is so not,” says Elizabeth Currid-Halkett, a professor of public policy at USC and the author of The Sum of Small Things: A Theory of the Aspirational Class. We’re looking for things “that make us feel like us again, that make life feel joyful again—and consumption is a straightforward way to do that.” It’s also a way to show off. McMullen says that body-baring pieces from Jacquemus and Khaite are doing particularly well for her, perhaps spurred by her customers’ home fitness efforts during quarantine. When we speak, she’s in New York meeting with designers, and finds herself defaulting to the refrain: “Do you have a few shorter hemlines?”

We’re all imagining ourselves to be post-metamorphosis butterflies, with brand-new wardrobes instead of wings. And Currid-Halkett doesn’t discount the emotional impact of adopting a new look. People, she says, “haven’t even had the natural social affirmation of walking into a restaurant and feeling attractive and alive.” A surge of splurging is understandable after 18 months of uncertainty and isolation. But the focus on consumption also feels like backsliding after the fashion industry’s recent paeans to sustainability, minimalism, and buying only what you need. Perhaps we’re in a moment where those more highbrow concerns are (at least temporarily) being thrown aside in favor of excess. Currid-Halkett points to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, which builds from basics (food, shelter) to more lofty ambitions at its pinnacle. “Self-actualization is the endgame, and a lot of us are not there right now,” she says. “We’ve got much more basic needs.”

This article appears in the September 2021 issue of ELLE.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io