Co-authored by Bella Ren and Maurice Schweitzer

Social media often confronts users with difficult choices: sharing unverified content that would generate social engagement, or sharing content that they know is more likely to be true but is less likely to be “liked.” Put differently, the decision to share conspiracy theories for many people reflects a calculated trade-off.

The spread of conspiracy theories has significantly limited our ability to deal with crises, from addressing climate change to fighting the COVID-19 pandemic. More than 70 million Americans who are eligible for a vaccine have chosen not to get one and approximately half of these people have misinformed beliefs, such as the belief that the government is using vaccine injections to insert microchips into people.

Beyond Beliefs

A growing body of work has begun to advance our understanding of why people believe in conspiracy theories. This work has found that people who feel like they lack control over events, and who dislike uncertainty and ambiguity are more likely to believe in conspiracy theories.

Many questions remain, however, with respect to why people share conspiracy theories. Although early work presumed that people on social media share content that they believe, our new research reveals that people are often willing to share conspiracy theories that they know to be false. In fact, we found that 40 percent of participants admitted that they would be willing to share conspiracy theories that they know to be untrue.

Why?

It turns out that when many people share information they care about broadcasting information that will boost their social engagement. We found that when the social rewards (such as the number of “likes” people received) were high, many people were willing to share conspiracy theories that they knew to be untrue.

We Share Misinformation for Social Connections

Conspiracy theories, compared with factual news, triggers higher emotional arousal. This makes conspiracy theories particularly attractive for generating social engagement. Consider the following example: a choice between rebroadcasting two posts. One post reports that Princess Diana died in a car accident. The other post reports that the royal family secretly plotted to murder Princess Diana and her lover. One post is more likely to be true. The other is far more engaging, more likely to grab attention, and more likely to trigger a reaction.

In one of our experiments, we varied the motives for the content people shared. In one condition, we paid participants a bonus for sharing information that would generate more “likes.” In another, we incentivized posts that would generate more comments. In a third, we paid participants a bonus for sharing accurate information.

What content did people share?

When we incentivized sharing content to generate social engagement (“likes” and comments), nearly 50 percent of participants shared posts about why the moon landing was fake, UFO spacecraft in Area 51, or how COVID-19 is an engineered bioweapon. When we rewarded people for sharing accurate information, however, nearly all of them shared posts about the 2021 U.S. capitol attack, global warming, and racially motivated violence. From this study, we found that people can separate fact from fiction—and that they expect fake news to generate more comments and more likes.

People Readily Share Conspiracy Theories

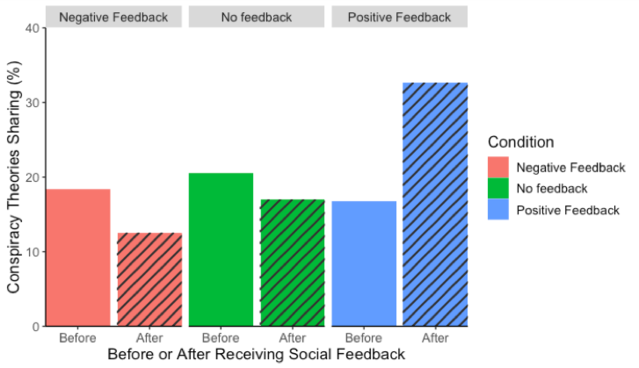

We also found that people are ready to share fake news even without monetary incentives. We created a social media platform that simulates how people interact in online social environments. In this platform, participants shared posts and received feedback from others across multiple rounds. In our experiments, we modified the feedback they received.

When we gave people on the platform more positive social feedback (i.e., more “likes”) for sharing conspiracy theories, the percent of people who shared conspiracy theories almost doubled after only a few rounds of interaction. That is, we found that people are incredibly sensitive to the social feedback in their environment. As soon as they found that sharing misinformation would generate more “likes,” they sacrificed accuracy in pursuit of social feedback and attention. Of course, our experimental setting differs from real platforms in many ways. For example, the reputational consequences for sharing misinformation was lower in our experimental setting. Still, our findings reveal that the decision to share misinformation may be surprisingly sensitive to social incentives.

Taken together, our findings identify social motives as an important driver of the decision to share conspiracy theories. Anticipating greater attention and engagement, individuals may choose to share posts that they know to be untrue. Ultimately, by sharing misinformation people may shift their beliefs and those of others. As a result, policymakers may be able to curb the spread of misinformation by simply shifting incentives for social engagement by shutting down bots that “like” and retweet misinformation and encouraging official institutions to support true news.