(The second part of a two-part post. Click here for the first part.)

This is what I wrote about Roswell in Intimate Alien: The Hidden Story of the UFO:

“Who are the extraterrestrials in the Roswell myth? They’re embodiments of death in its aspect of alienness, as the redheaded captain and the black sergeant [who harass and terrorize witnesses to the UFO crash] embody it in its aspect of raw terror. They’re also ourselves, frail helpless children confronted by a calamity we can neither grasp nor ward off.”

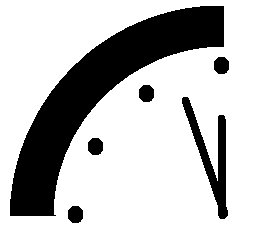

By this “calamity,” I meant first and foremost our individual deaths. But there was something more to Roswell, special to its time and place, “a new sort of death, a recent arrival to this world when Roswell made its first brief splash” in July 1947. The Doomsday Clock, ticking away the minutes to nuclear annihilation, had just made its appearance on the cover of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

“Death had always been with us; so had visions of the end of the world. But this ‘end’ normally meant the deliberate intervention of a benevolent God, a ‘new heaven and a new earth’ to follow. Now Doomsday was no ‘Judgment Day’ (the original meaning of the word doom), but pure annihilation, pure desolation. It would leave behind only empty sky and barren earth, God and the human spirit dead in tandem.

“Translated from the mythic symbolism, this is the meaning of Roswell: Child-humanity, dreaming of heavenly dominion, crashes to permanent extinction.”

And now Jacques Vallee and Paola Leopizzi Harris, in their new book Trinity, bring to our attention another UFO crash story which they treat as distinct from Roswell, but which I’d like to understand as a different version of the same myth, in which Roswell’s latent allusion to nuclear annihilation is made absolutely clear and explicit.

Let’s test this understanding with a close look at two elements of the story that Vallee and Harris put before us–set in August 1945, exactly one month after the apocalyptic nuclear blast, at the Trinity Site in the New Mexico desert, that changed human history forever.

1. The aliens as children. “They moved fast, as if they were able to will themselves from one position to another in an instant,” Remigio Baca told Ben Moffett in 2003, describing the beings that he and Jose Padilla saw inside the crashed UFO. “They were shadowy and expressionless, but definitely living beings. … They seemed to us like children, not dangerous.”

Seven years later, Baca gave a similar account to Paola Harris. “I was looking through the binoculars at these little creatures moving back and forth … like, sliding.” He immediately corrects himself: “Not sliding, but more like willing themselves from one place to another. … And as I’m looking at that, things began happening in my mind. … I’m seeing them and I’m feeling this crazy stuff, like I really feel sorry for them … like they’re kids, too.” He hears a high-pitched sound from the object, and associates it with the sound of “jackrabbits when they were in pain, and also the sound that comes out of a newborn baby when it cries.”

Later he repeats the point: “They kinda look like kids, very strange kids.” And again: “Jose and I were looking at the craft through one set of binoculars, we were taking turns. He was looking, but we couldn’t directly look into their eyes, that I can remember, it’s pretty far, I know, but what we felt was this pure sorrow, really felt sorry for them because we could feel their pain. They seemed like us, children” (p. 37).

I’ve blogged in the past (here and here) on the Roswell aliens as having been, at the level of the unconscious, children. I’ve woven this theme into my 2011 novel Journal of a UFO Investigator. “They were children, Danny,” I had my character Rochelle tell the novel’s protagonist about the alien corpses at Roswell. I’m naturally excited to hear Baca say the same thing, in almost exactly the same language.

But there’s a complication. However long Baca and Padilla’s story may have gestated within them, it first surfaced in 2003–long after Roswell had become a household word. The two men had ample opportunity to saturate themselves with the testimonies of the Roswell witnesses. And in fact one of these witnesses, the doubtfully reliable Gerald Anderson, told in 1990 or thereabouts a story of his encounter (as a five-year-old boy) with a crashed UFO that sounds so close to Baca’s, even in its language, that it’s hard for me to believe Baca wasn’t drawing on it.

“And all of a sudden it [the one surviving alien] just turned and looked straight at me between my uncle Ted and myself. And this is when–it was just like an explosion of things in my head, things… I just started, you know, feeling, just terrible depression and loneliness and fear and just, you know, awful, awful feelings that just suddenly burst into my mind there. I don’t know if that meant that it was communicating with me and I was the only one there that it could communicate with because I was a kid. I don’t know.” (Quoted by James McAndrew from the raw footage used for a 1993 video on Roswell.)

In December 1990, Anderson told a reporter from a Missouri newspaper something very similar (quoted in Randle, Roswell in the 21st Century, p. 335). “I felt that thing’s fear, felt its depression. I relived the crash. I know the terror it went through.”

In the first part of this post, I called attention to one aspect of the Baca-Padilla story–the official explanation of the fallen body as a weather balloon–that seemed to have been transferred from the Roswell story, where it made sense, to this new context where it makes no sense at all. Kevin Randle, writing early this past June, gives other examples of details that seem to have migrated into this story from Roswell, noting that “this suggests contamination rather than corroboration.”

Yes indeed. But in the case we’re considering there seems to be something more, that can’t be explained solely as “contamination” of Baca’s narrative from Anderson’s. The equation of the wounded alien with the frightened five-year-old witness is implicit in what Anderson describes, but he never says it openly. Baca puts it right out on the surface. And he adds a striking detail that has no parallel in Anderson’s testimony: the comparison of the alien’s pained cry to the wailing of a newborn infant.

(Come to think of it, doesn’t the “avocado”-shaped UFO remembered by Baca and Padilla sound a bit like the womb, from which these “children” come flitting forth?)

So Randle is certainly right: Baca told his story already knowing the details of the Roswell traditions. They’d become incorporated into his own unconscious to such an extent that they seemed to him memories of what he and his friend Jose had literally experienced, and he reported them as such. But in making them his own, he also interpreted them, bringing out what was latent within them.

In my opinion, he did so correctly and well.

2. An eerie chill. Jose Padilla’s niece Sabrina was born in 1953, too late to have witnessed the crash. But she claimed to remember from her childhood some of the artifacts that her uncle had retrieved from it, and late in 2020 she described them to Paola Harris.

I’ve already quoted Sabrina’s description of the tinfoil-like stuff that would spring back to its original shape no matter what you did with it, and the strange, sinister “angel hair” that felt like “a bunch of little razors touching you.” There was something else too: a kind of small metal pyramid that was “light as a feather” but so strong as to be indestructible. “And it would stay cold, a lot of time” (p. 263).

She’d already made the last point, at greater length, in an earlier interview. “That piece of metal, you know, that piece of metal would stay cold on a hot day. … I remember when I would get the piece of metal it was, like summer time, in New Mexico it’s hot over there. … But uh, I remember when it was real hot, you could put that piece of metal onto your face and it would be cold” (pp. 243-44).

In this detail, too, I hear an echo of Gerald Anderson. It was “very, very hot,” Anderson told an interviewer, the day he encountered the crashed UFO. “Incredible to me, being the first time in New Mexico and coming from back east. … It was like the inside of an oven.” And yet the closer he got to the UFO, the cooler it was. “And standing under it in the shade there next to these creatures’ bodies, it was like refrigerated air conditioning.”

Anderson touched the object. “What did it feel like?” the interviewer asks; and Anderson replies, “It was ice cold. It felt like it just came out of a freezer.” (From McAndrew, p. 190.)

Most UFOlogists discount Anderson’s testimony, regarding him (for good reason) as a liar and hoaxer. But this detail hardly sounds like something a hoaxer would invent, and McAndrew points out that it bears the mark of authenticity. For McAndrew, the Roswell-centered stories of crashed UFOs with bodies inside were not fabrications or fantasies, but distorted recollections of actual events: Air Force experiments in which scientific equipment was ballooned high up into the atmosphere, along with human-like dummies, and then allowed to fall to earth. In this context, Anderson’s recollection of “ice cold” metal makes perfect sense. It “accurately describes a physical condition known as ‘cold soaking’ common to high altitude payloads that had recently been exposed to sub-zero temperatures of the upper atmosphere” (McAndrew, p. 64).

So the eerie, inexplicable chill of the metal described by Sabrina Padilla in 2020 is a borrowing from the testimony of Gerald Anderson thirty years earlier, which is in turn–if McAndrew is right, and I think he is–based on an actual event in the New Mexico desert some forty years before that?

If so, is it something she genuinely believes herself to recall? Or something she made up, based on her media-derived knowledge of Roswell, to please and impress Paola Harris? (Whom she seems to regard with some awe, as a personage superior to herself and those among whom she lives: “I just want to tell you, Miss Paola, that I appreciate people like you that, you know, take time to…with people like us.”)

Either option is possible, though I incline toward the former: that the preternatural chill of the alien metal, migrating from the Roswell traditions, has become rooted within Sabrina’s own memories of her childhood. The question then demands to be asked: Why? What did the detail mean to her, that she felt moved to incorporate it as her own?

And for this one, I’m afraid, I have no answer.

By and large, I think my initial impression of Vallee and Harris’s Trinity is correct. It’s important and valuable, though not for the reasons its authors believe it to be. It’s important in that it presents a version of the Roswell myth that draws out, makes explicit, says in so many words what’s latent and concealed in the more normative versions–that, at its heart, the myth is not about Roswell 1947 but the dreadful event at Trinity 1945.

I may have gone too far when I called it a “variant.” Do you apply the word “variant” to a myth that’s been transmitted by a total of three people (Remigio Baca, Jose Padilla, Sabrina Padilla)? That has never gotten significant traction and, if the tepid response so far to the Vallee-Harris book is any indication, is unlikely to get traction now? (Vs. the mainstream Roswell tradition that, as I wrote in Intimate Alien, is “known the world over as the most hauntingly familiar fairy tales are known.”) That shows frequent marks of its dependence, not only of its themes and images but even of the language it uses to express them, on the normative Roswell literature?

It would be wrong to speak of the Roswell crash and the Trinity crash as if they were co-equal branches of the same mythic tree. Rather, Roswell is the trunk, Trinity a puny twig branching off it. Yet it’s a twig which, examined carefully, can teach profound and important lessons not only about the trunk of the tree, but also its roots.

Which is why Vallee and Harris’s book, for all its flaws, turns out to be a precious addition to the literature of the UFO.