Colby Landrum: ‘If I could get some closure . . .’

A fresh splash of asphalt on the road where it happened, Highway 1485, outside Dayton, Texas, from 1983.

We were both on the front end of things, back then – me in newspapers, Colby Landrum as a reluctant young media celebrity. Maybe I should’ve paid more attention to his demeanor than to his words. It wasn’t like he was going to say anything he hadn’t already told millions before on national TV. His grandmother and legal guardian, Vickie, stayed in the living room, no need to coach the boy at this point.

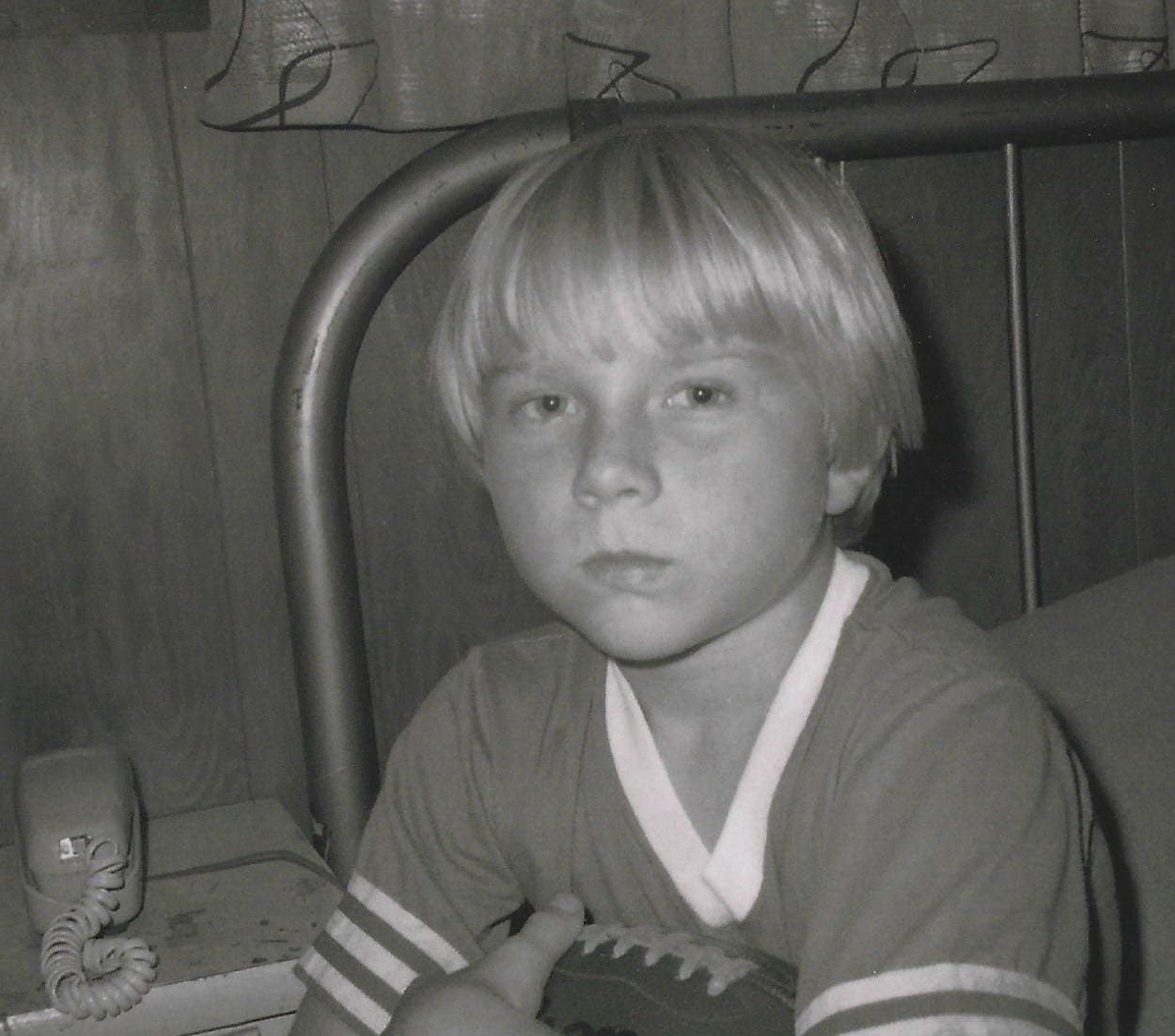

I wrote that he twiddled a flyswatter between his toes as he sat on the edge of the bed in the room he shared with his cousin. I noticed the rims of his eyes were slightly pink, as if he’d “been swimming in chlorine.” Nine years old, maybe a tad small for his age – Vickie said she’d had trouble getting food in him lately.

I pressed the record button. His version of the events that forever rocked his world along a rural stretch of highway outside Houston on Dec. 29, 1980, spooled onto Side A of the audiocassette. Colby talked dispassionately about the heat-spewing UFO, the flanking military helicopters, and the immediate aftermath, the nightmares that woke him up crying. “Every night, I’d vomit a whole buncha times,” he recalled in a monotone, “and they’d have to keep a pan in my room.”

His eyes narrowed when I asked if he thought he’d ever learn the truth. “We’re gonna find out what it is,” Colby vowed. “I don’t care how long it takes – we ain’t giving up ‘til we find out what it is.”

I wondered, as we wrapped it up, if maybe I could get a few photos. I wasn’t a shooter, the paper was getting this story on the cheap, as usual. But by now, Colby was a pro – “You want me to hold my football or something?” I interpreted his dutiful but unsmiling accommodation as poise. A few clicks and we were done. September 1983.

I woke up one morning and I was 39 years older. The adults who were in the car with Colby — grandma and driver Betty Cash — were long gone. But American history had become unmoored from its traditions; all of a sudden, Congress was acting serious about UFOs and national security. And I wanted to know if Colby had any hope left.

The voice on the phone agreed to meet, but told me to lower my expectations, that things had gone “sideways” for him lately. “It could be raining vaginas,” he muttered, “and I’m gonna get hit with one dick right between the eyes.” Whatever I was swallowing came spraying out my nose. But Colby wasn’t laughing.

I rummaged through some filing cabinets and discovered the negatives from 1983. I got them developed and studied the black-and-white prints as if for the first time. Staring back was something I’d short-shrifted back then, the face of a kid who’d been through the wringer was — for better or worse — toughening up. And for everything he’d said in the 20th century, his expression back then signaled that he was also holding back.

Easter weekend, two weeks ago: In the living room at his latest address, in Clinton, west Oklahoma, population 9,000, Colby Landrum pulled up a chair, contemplated the image of the bullied child he once was, and began filling in the back story.

“I didn’t tell nobody about it because everybody was saying, well, if we said something it might go bad on us, so I didn’t wanna be telling all the kids at school. But then,” he continued in his Lone Star drawl, “it all came out on TV, and of course all the kids took it however their parents rolled, y’know? People started messing with me and I took a lotta heat and eventually it just got to the point where, when they embarrassed me, I’d jump on ‘em. I was getting in fights left and right – I’d fight at the drop of a dime.

“People said look, it’s that alien kid, he got abducted by aliens or whatever. They automatically went to the alien shit because the tabloids had loaded up on it.”

Bullied in school following the 1980 UFO encounter that made international headlines, a 9-year-old Colby Landrum vowed to discover what happened back then, “I don’t care how long it takes.”

We were nearly a month into spring, but on this day, winter hung on for dear life, leaden skies whipping raw winds into “feels like” temps in the 40s. Down and out, Colby had moved into this house two years ago to be with relatives. After high school, he learned welding, became a pipefitting a supervisor, and was pulling in $100k a year outside Houston; today, in Oklahoma, the roller coaster was parked and he was earning subsistence wages by “laying asphalt.” He talked about maybe someday returning to his roots in east Texas, where suburban sprawl is swallowing the scene of the accident, or crime, or whatever it was. For now, stability is its own reward.

I asked if he had heard about the roughly 1,500 pages of documents just released by the Defense Intelligence Agency, or the secret AAWSAP/AATIP initiatives in the Pentagon, or the new congressional language legislating UFO accountability from an insulting Defense Department acronym called AOIMSG (Airborne Object Identification and Management Synchronization Group). It was all news to Colby. I asked if he’d read the landmark New York Times story in 2017, or if he’d seen the accompanying F-18 jet fighter videos.

“I’m almost embarrassed I ain’t followed this shit,” he said. “It’s almost like I’m afraid to, like if I do, things might start coming back up on me. It’s like – OK, I been here for two years now, knowing these people, and you don’t want ‘em to look you up on the Internet and … you know? The people I kinda like and trust, I say, hey, just so you know? If you look up my name, you might kinda freak out.”

I showed him the lengthy Defense Intelligence Reference Document (DIRD) titled “Anomalous Acute and Subacute Field Effects on Human Biological Tissues,” produced in 2009 but only now released through FOIA. It was commissioned to analyze “evidence of unintended injury to human observers by anomalous advanced aerospace systems.” It argued that continued work on such injuries “can inform (e.g., reverse engineer), through clinical diagnoses, certain physical characteristics of possible future advanced aerospace systems from unknown provenance that may be a threat to the United States interests.”

In other words, according to the 31-page report prepared by former CIA forensic scientist Dr. Christopher “Kit” Green, a complete analysis of those injuries might yield enough details to produce the schematics for replicating whatever it was that created those injuries in the first place. Colby didn’t say much. “I’m listening,” he said.

I pointed out the DIRD’s specific references to the “Cash-Landrum Incident,” as well as the report’s mention of the 1996 “Schuessler Catalog of UFO-Related Human Physiological Effects.” John Schuessler, co-founder of the Mutual UFO Network, had compiled a list of 356 worldwide close-encounter cases, dating back to 1873, in which observers’ health had been altered by exposure to high strangeness. And Schuessler was a name Colby knew well.

An aerospace engineer at Johnson Space Center, John Schuessler was the first researcher to take the story seriously back in early 1981. Thanks to the outstanding archival work of Curt Collins, a virtual library of what happened is available at Blue Blurry Lines. It’s packed with primary-source material, handwritten notes, niche-journal articles and a mixed bag of medical opinions, some of which blamed radiation for the injuries, others citing exposure to chemicals.

On file are photocopies of Betty Cash’s scalp visible through clusters of ragged hair that hadn’t yet fallen out, Vickie’s ghastly skin lesions, letters from Texas senators John Tower and Lloyd Bentsen directing the victims to contact the Judge Advocate Claims Officer at Bergstrom AFB. Also included are links to contemporaneous media coverage, from the lowbrow Weekly World News (“3 Survive UFO Attack”) and The National Enquirer (“UFO Terrorizes and Burns Three in Car”) to local splashes in the Monroe Courier, the Houston Chronicle, KHOU-TV.

Bits and pieces of the mystery – ABC’s “That’s Incredible!” and “Good Morning America,” HBO’s Undercover America, “Sightings” on Fox, NBC’s “Unsolved Mysteries” – were heavily popularized during the Reagan years. Betty’s story was the most gruesome. She told of being sequestered in a room at Houston’s Parkway Hospital where attendants initially wore hazmat gear. Her daughter described seeing her unrecognizable mother in the hospital for the first time, raw skin peeling from her swollen face and arms, boils and bursting watery blisters, everywhere, inside her nostrils, inside mom’s eyelids. Betty never recovered. She gave up the diner she owned, moved back to Alabama to be with relatives, and spent the rest of her life getting bad medical news. She died in 1998 at 69.

By 1982, the story had generated enough buzz to prod an investigation from the Department of the Army’s Inspector General. That’s because the witnesses reported the UFO was accompanied by double-rotor helicopters, CH-47 Chinooks, possessed only by the Army.

The paper trail includes a buzz-off note from the DAIG to then-freshman congressman Ron Wyden – now on the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence – assuring him that no Army assets were involved in the incident. The three-page results of the IG’s official query (with redactions) state the witnesses were “credible,” and that there was “no perception that anyone was trying to exaggerate the truth.” Furthermore, “the medical evidence of deterioration of health seems almost irrefutable.”

But the IG’s job was to get the Army off the hook, not to identify the UFO or the cause of the injuries, which included “blackened fingernails, constant diarrhea, and diminished eyesight.” Concluded IG Lt. Col. George Sarran, “There was no evidence presented that would indicate that Army, National Guard, or Army Reserve helicopters were involved.” In 1985, a federal judge tossed a Cash-Landrum bid to sue Uncle Sam for damages, citing lack of evidence.

There’s a remarkable link to a UFO Hunters episode from 2009, two years after Vickie died at 84. The producers arranged for the first face-to-face meeting between Sarran and the sole survivor, Colby Landrum.

On the show, the retired Sarran restated the findings from his ‘82 verdict. “Twenty-three helicopters would be a real logistical operation, being so close to a major international airport,” he told UFO Hunters. Houston International, located less than 30 miles from the Dayton area, could offer no corroborating radar evidence of the event. Nor did flight records from any regional Army-connected facilities indicate they had birds in the air that evening.

When UFO Hunters confronted Sarran with his own handwritten notes, acquired through FOIA, which stated “100 helicopters – Robert Grey (sic) airfield, came in, for effect,” Sarran had no answer. “I …” he paused. “I have no idea why I might have wrote that down.”

Thirteen years after that History channel episode aired, Colby still chafes at the colonel’s response: “I wanted to whip (Sarran’s) ass.”

Robert Gray Army Airfield is adjacent to Fort Hood, home to the Army’s 1st Air Cavalry Division, just under 200 miles from Houston Intercontinental. Researchers agreed that only Fort Hood could’ve mobilized enough hardware to stage an operation of the magnitude described by Cash-Landrum. But they weren’t the only ones reporting military helos in the vicinity on the evening of 12/29/80. A handful of Dayton-area residents, including a police officer, stated they’d seen double-rotor helicopters in the mix as well, lights blinking, flying low, as if hunting for something.

On a living room wall rests a small shrine to Colby’s late grandfather Ernest. The shelf hosts a folded American flag, a portrait of the aging Army veteran, an old watch, and a Purple Heart from World War II. “That man up there, he almost give his life for this country,” Colby says. “Yet, he had to sit there and watch my grandmother go through everything she went through. And the government he fought for calls us liars.”

Details dim in the fog of memory, but the spectacle lingers: Around 9 p.m. on 12/29/80, Colby was wedged between Betty and Vickie in the front seat of Betty’s new Cutlass Supreme. Vickie worked for Betty as a waitress at Betty’s diner, and the two were in futile search of a bingo game in the shuttered space between Christmas and New Year’s. As they headed for home on two-lane 1465 cutting through a pine forest, Colby was the first to see it.

“It looked like just a big ball of fire coming over the trees, and the trees on both sides of the road were about 100 foot tall, so it was clearing that and then some, maybe 80 feet, I don’t know.”

Betty hit the brakes as the thing began to cross above the opening in the straightaway ahead, illuminating the woods below. But Colby had his eyes on the helicopters.

“As a kid, I was obsessed with Army-type things, so that’s what I’m focusing on. Betty and grandma were talking about the object, but I didn’t think it was scary because the helicopters were there. And when they seen the helicopters they pulled up a little bit farther.”

Betty nudged the Olds maybe 100 yards ahead before stopping the car again amid a blaze of heat. Betty said she had to turn on the air conditioner “to keep from burning up.” Vickie would leave her left handprint in the dashboard. Colby remembers the object on a leisurely course, “like a blimp,” but he kept watching the choppers. “I counted 23 of ‘em, double-rotor deals,” Colby said. “And they were in formation, like they were rounding up cattle or something.”

Afraid to go farther due to the heat, Betty opened the door to get out for a better look. Vickie climbed halfway out the passenger side. Both women described a diamond-shaped object making beeping noises and belching flames from its belly, seeming to right itself with each “whooshing” blast, as if experiencing stability problems. Colby said he never got that good a look because “my grandma started hollering ‘Jesus is coming back!’ and told me to get down on the floorboard. And that’s what scared me.” The women watched for what seemed an eternity to Colby – 10 minutes? 15? Longer, maybe?

Vickie ducked back inside first. Betty tried opening the door handle but burned her hand, and had to use her coat for a grip. As the weird fleet moved on – “They looked to be in no great hurry,” Colby said – he, Betty and Vickie drove ahead and kept watching until they turned toward home and the air show disappeared over the horizon. End of encounter. Within hours, he and grandma began experiencing varying signs of trauma. They checked Betty, immobilized on her bed, into the hospital a day or two later.

As the news found a mass audience, speculation flourished in the vacuum, ranging from space aliens to a secret nuclear propulsion experiment that jumped the rails. Hacks like Aviation Week reporter Philip Klass weighed in: “I believe the story is a hoax. There is absolutely no evidence. The women’s story is supported only by the claim of Betty Cash that she had serious health problems after the alleged incident.” For fellow debunker James McGaha, the Army’s final word was good enough: “The military, in my experience, does not lie.”

And then there were peculiar parallels with the so-called Rendlesham Forest Incident, which unfolded at a U.S. air base in southeast England just days, perhaps even hours, before the Cash-Landrum encounter. Over consecutive evenings between Christmas and New Year’s 1980, officers and NCOs alike reported interactions with glowing UFOs in the woods near the installation, which warehoused tactical nukes. Some witnesses experienced radiation-related health problems; former Air Force MP John Burroughs, for instance, is unable to look at his own service-connected medical records because they’ve been classified for 42 years.

All of which begs the question: Did Colby have health concerns he could connect with 12/29/80?

“Well, right afterwards I was pretty sick, I mean, I was itching a lot, I felt like a poisoned rat, like I was burning up inside. My whole body was feverish and cold all at once. It’s hard to explain,” he said. “But remember, I was down in the floorboard for most of it, so I was kinda protected.”

Colby’s had dental issues and kidney stones, and there are a couple of bumps on the back of his head “I need to get to.” But nothing he’s willing to blame on the encounter. “Anything long-term, it would’ve killed me by now, right?”

So far as he can remember, no one ever drew blood samples – “I was afraid of needles, I think I would’ve remembered that” – but he suspects he was tested for radiation. Decades ago, some strangers came out to the house “and they had these little black bags that you stick your hand in or something, it was weird … All I remember is a metal box and a black deal that went over your hand when you stuck it in there. Like a shiny silver metal box.”

But then, some things never crop up in lab results, things he’d rather keep to himself, guilt over things he can never recover. He thinks about Misty, his wife, killed in a car wreck in 2009, and fatherhood has been a challenge. The what-ifs don’t really matter anymore, but he’d stand a better chance of losing his own shadow.

“Had that (UFO) encounter not happened? Maybe I would’ve lived a normal life without being set up as this crazy kid at 6 years old. Maybe it affected the choices I made, I don’t know, maybe I would’ve had a little different life.” He paused. “Probably not.” Shrug. “We live by the choices we make, right, so it’s all pretty much on me.

“Did it mess my head up along the way, though? Yeah, I’m sure it did. But one thing you better learn early on is, you better fix it yourself or else it ain’t gonna get fixed. If I could get some closure, that might make it better.”

There’s a plaque on the wall, words arranged in the shape of a cross: “Amazing Grace, How Sweet the Sound.” Colby lights a cigarette and looks off into the middle distance.

At home in Clinton, Oklahoma, 48-year-old Colby Landrum, says Uncle Sam owes him an apology for making him look like a liar.

“I don’t believe in —look, I’m sure they’re out there. But unless it affects my life right now at this moment, I’m not gonna read into it. But whatever hurt me didn’t have little green men in it. Whatever it was, was being controlled by our people. It was not out of control. And there’s a record of it somewhere. There’s records on everything.”

Closure?

“Apologize. Say, ‘Look man, this is what happened. We couldn’t tell the whole world but we had something going on that would’ve probably freaked everybody out, but you’re not crazy.’

“That’s what I want to hear. I don’t need no money. The money ain’t gonna do me no good. Make right by my family and tell us what the hell’s going on.”

The future? An ideal situation?

“I don’t set goals anymore. It’s hard to set two weeks in advance, to be honest with you. I just go day to day and try not to look back.”

But if?

Without hesitation: “I’d like to work with the homeless, to be honest with you. There’s people out there that don’t have any options at all. I’d like to see what I could do to help people like that.”