The Welsh legend of Cantre’r Gwaelod, a lost land sunken below Cardigan Bay, has persisted for almost a millennium.

First written about in the mid-13th Century, it is likely the myths and legends surrounding the Welsh Atlantis date from long before that.

Yet there has never been any definitive geographical evidence for the mythical land… until now, perhaps.

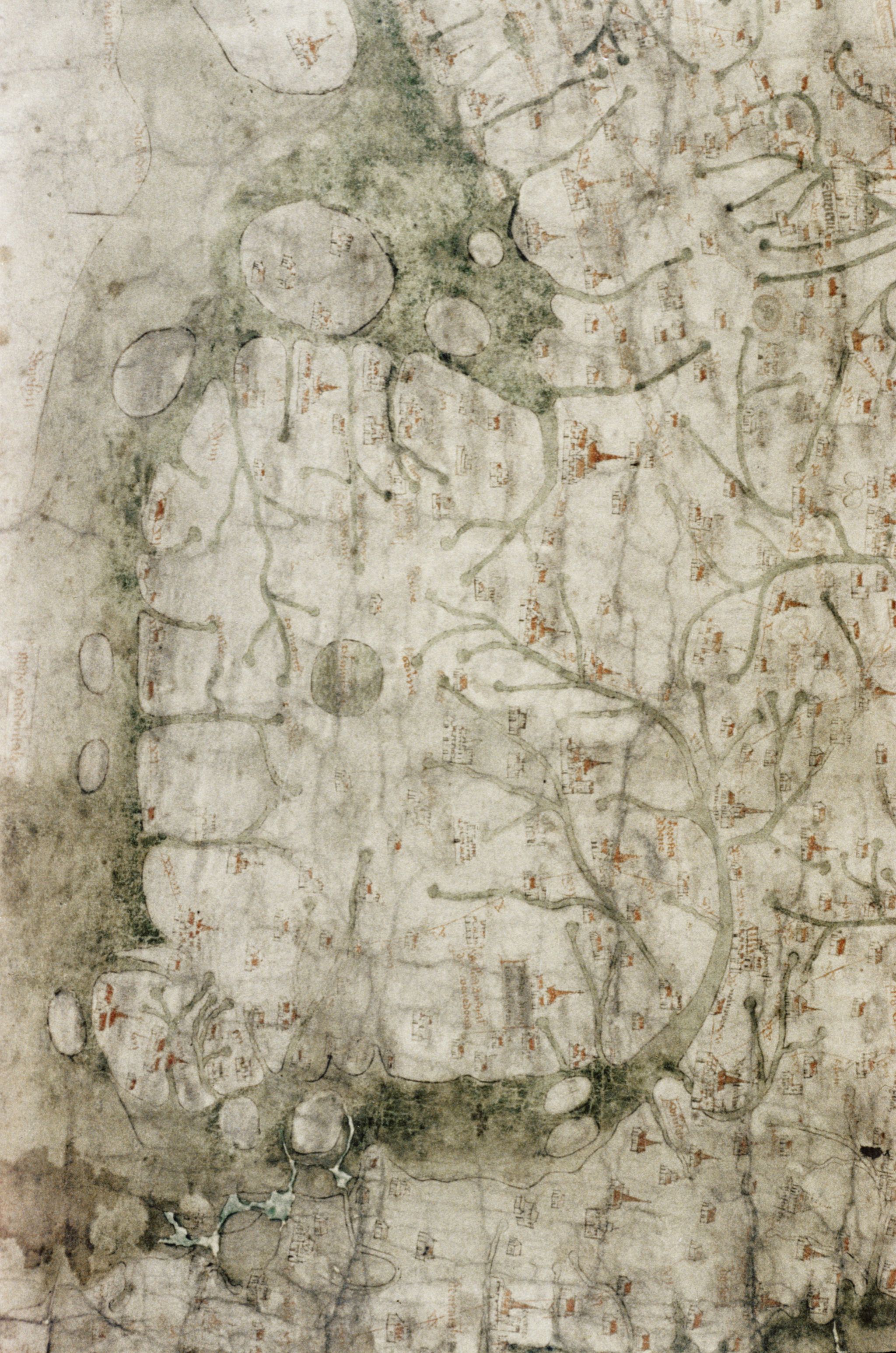

A medieval map has been uncovered which depicts two islands off the Ceredigion coast – now lost to history.

Simon Haslett, honorary professor of physical geography at Swansea University, went in search of lost islands in Cardigan Bay while he was a visiting fellow at Jesus College, Oxford.

Along with David Willis, Jesus Professor of Celtic at the University of Oxford, they have presented evidence of two islands depicted on a medieval map, each about a quarter the size of Anglesey.

One island is offshore between Aberystwyth and Aberdyfi and the other further north towards Barmouth, Gwynedd.

Prof Haslett explained that the two islands are clearly marked on the Gough Map, the earliest surviving complete map of the British Isles, dating from as early as the mid-13th Century.

“The Gough Map is extraordinarily accurate considering the surveying tools they would have had at their disposal at that time,” he said.

“The two islands are clearly marked and may corroborate contemporary accounts of a lost land mentioned in the Black Book of Carmarthen.”

The map is held in the collections of the Bodleian Library at Oxford University.

Cardiff University’s Welsh folklore expert Dr Juliette Wood – who was not involved in this research – said the Black Book’s account was key to anchoring the story in Welsh myth.

“The Gough Map may have its origins around 1280, shortly before that, around 1250, you have the Black Book of Carmarthen.

“It describes Gwyddno Garanhir’s country called Maes Gwyddno (Gwyddno’s Field). It was flooded because the well-keeper (Mererid) left the cover off the well.”

Fact within folklore?

Drawing upon previous surveys of the bay and understanding of the advance and retreat of glaciers and silt since the last ice age about 10,000 years ago, Profs Haslett and Willis were able to suggest how the islands may have come into existence and then disappeared again.

Prof Haslett also suggested it may explain some of the local folklore.

He said: “I think the evidence for the islands, and possibly therefore the legends connected with them, is in two strands.

“Firstly, coordinates recorded by the Roman cartographer Ptolemy suggest that the coastline at the time may have been some 13km (8 miles) further west than it is today.

“And, secondly, the evidence presented by the Gough Map for the existence of two islands in Cardigan Bay.”

He added folk legends of being able to walk between lands now separated by sea could be a folk memory stemming from rising sea levels after the last ice age.

“However, legends of sudden inundation, such as in the case Cantre’r Gwaelod, might be more likely to be recalling sea floods and erosion, either by storms or tsunami, that may have forced the population to abandon living along such vulnerable coasts,” he added.

“In roughly a millennium, from Ptolemy’s time to the building of Harlech Castle during the Norman period, the seascape had completely altered.”

“Later maps show the islands had disappeared, yet further up the coast at Harlech, the castle which was built to have a strategic advantage on the coastline now found itself more or less landlocked,” he added.

“The erosion of any islands here would have released boulders that are likely to have contributed to the accumulation of the distinctive stone structures known locally as sarns.”

Dr Wood believes these sarns have played a vital part in perpetuating the story.

- WALES’ HOME OF THE YEAR Which home will Owain, Mandy and Glen judge worthy?

- IOLO: A WILD LIFE: Iolo delves into the archives from the past 25 years

‘Re-enchanting the land’

“People now as much as then want to find a way of explaining things which seem simply unexplainable; especially during tough times,” she said.

“I’ve seen the sarns myself, and they are incredibly convincing. You could easily believe that their uniform structure was once part of a lost civilisation, however the catch is that most of these stories don’t come back into fashion until the 18th Century.

“I call it re-enchanting the land, the romanticists amongst the Celtic population want to find meaning and a belief system to make sense of the current hardships.”

Dr Wood added that similar “Atlantis” legends can be found around most of the world, particularly in Europe.

“These migratory stories emerge when the facts fit the myth. They come and go all over the place, but especially when phenomena like the sarns appear.

“Rather than saying that the discovery of the island proves the folklore, I’d say that the proof is coincidental, and that the two truths can exist independently of each other.”

However, Prof Haslett warned his findings could have more bearing on the future than the past.

“These processes didn’t happen just once, they’re still on-going.”

“With rising sea levels and more intense storms it’s been suggested that people living around Cardigan Bay could become some of Britain’s first climate change refugees, within our lifetimes.”

- Profs Haslett and Willis have published their findings in the journal Atlantic Geoscience

-

-

19 June 2012

-

-

-

12 January 2013

-