By Douglas Dean Johnson (@ddeanjohnson)

Posted December 6, 2022, 11:30 PM EST. Latest update: December 8, 2022, 1:45 PM EST.

The PDF document embedded below contains all of the UAP-related provisions found in the version of the Fiscal Year 2023 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) that was filed by congressional negotiators late on Tuesday, December 6, 2022 (H.R. 7776, House Rules Committee Print 117-70). The House of Representatives passed it on Thursday, December 8, 2022, at 1:39 PM EST, by a vote of 350-80. The U.S. Senate is expected to take up the measure within a matter of days. I believe that final congressional approval and enactment are likely before the end of the year. The bill is not likely to be amended at all, and certainly not with respect to the provisions discussed here.

There are two main UAP related provisions, found in three numbered sections of the bill (Section 1673 and Sections 6802-6803). They are in many ways similar to the provisions seen in earlier versions of the NDAA, and in the Intelligence Authorization bills (which have now been wrapped into the NDAA), as I discussed in this detailed article published on July 14, 2022. However, in the ensuing months, members of the congressional security committees (armed services and intelligence committees) in closed-door negotiations have made some noteworthy refinements, which are reflected in the final text posted at the link above.

I may explore the new language in more detail in days to come. To receive email notifications of future articles on this blog, click the “Subscribe” button and enter your email address (it is free and will remain so).

For now, I will briefly summarize some of the key provisions, highlighting some of the changes from the earlier versions that jump out at me.

Bill Section 1673:

Secure Method for Authorized Reporting (“Safe harbor” or “UAP whistleblower” provisions)

This section (found on pages 1425-1434 of Rules Committee Print 117-70) creates a “secure method” by which current or former government employees or contractors can submit UAP-related information to the Pentagon UAP office, and through that office reach also the congressional armed services and intelligence committees.

The Pentagon UAP office was given a statutory foundation by the extensive UAP provisions enacted on December 7, 2021, as part of the the FY 2022 NDAA. (For those not familiar with the provisions of the 2021 law, sometimes called “Gillibrand-Rubio-Gallego,” codified at 50 U.S. Code § 3373, I recommend review of my detailed article of December 7, 2021, here.) Under the new bill, that office will retain its current name, the All-domain Anomalies Resolution Office (AARO, pronounced “arrow”), which it adopted by administrative decision earlier this year.

The secure-reporting provision originated in a closed-door voting meeting (“mark up”) of the U.S. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence (SSCI) on the FY 2023 Intelligence Authorization Act (S. 4503), on June 22, 2022. It was put forward as part of a substitute amendment advanced by SSCI Chairman Sen. Mark Warner (D-VA) and SSCI ranking Republican Marco Rubio (R-FL).

S. 4503 did not reach the Senate floor, but a similar amendment later was offered on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives to the House version of NDAA (H.R. 7900) by Reps. Mike Gallagher (R-WI) and Rep. Ruben Gallego (D-AZ); it was adopted, and that bill passed the House on July 14, 2022.

The essence of bill Sec. 1673 tracks what we saw in the earlier versions. Notably, Sec. 1673(a)(1)(B) contains new language that explicitly and expansively defines the scope of interest as “any activity or program…related to unidentified anomalous phenomena, including with respect to material retrieval, material analysis, reverse engineering, research and development, detecting and tracking, developmental or operational testing, and security protections and enforcement.”

Sec. 1673(b)(1) provides that those bringing information forward into the new system are not thereby committing any violation of the laws and executive order that govern classified national security information, nor to be impeded from that disclosure by any previously applicable non-disclosure agreement. These protections apply to information fed into the secure system, and do not authorize public disclosure of classified information.

Sec. 1673(b)(2)(A) is a sweeping anti-reprisal clause, applicable both to government employees and contractors. A provision of the SSCI-reported bill to grant a private cause of action for persons who feel they’ve suffered reprisal has been dropped, for reasons not entirely clear, but replaced with Sec. 1673(b)(2)(B), providing that the Secretary of Defense and the Director of National Intelligences “shall establish procedures for the enforcement” that are “consistent with” two existing laws that establish procedures to protect members of the military and the Intelligence Community who report possible wrongdoing (10 U.S. Code § 1034 and 50 U.S. Code § 32343, respectively).

Sec. 1673(a)(4)(B) contains a noteworthy requirement not seen in earlier versions: If AARO receives through the secure system a disclosure about a UAP-related restricted access program that had not previously been disclosed to the congressional defense or intelligence committees, “the Secretary [of Defense] shall report such disclosure to such committees and the congressional leadership” within 72 hours.

The question arises, is Section 1673 properly described as “whistleblower protection” legislation? I would say yes, in the sense that term is commonly employed, as referring to someone within government coming forward to bring possible wrongdoing to the attention of appropriate higher authorities. If someone with knowledge of a hypothetical government-funded UFO program, of which Congress was never notified as required by law, used the new secure system to bring that information to the attention of AARO and Congress, then I think that person would be properly described as a “whistleblower,” even though the term does not appear in Section 1673 (which speaks of “authorized disclosure”). The bill does provide robust anti-reprisal protections for such an individual.

There might be other cases in which a witness learns of the new system and uses it to provide obscure but useful information that had simply been lost, pigeon-holed, or forgotten, without any element of improper active concealment, and in that case the term “whistleblower” would not be a good fit – but the “secure method” would still be useful.

In this article, I do not discuss Sections 5204 and 6609 of H.R. 7776, which make multiple revisions to existing “whistleblower” laws covering the Intelligence Community. These sections represent a congressional response to certain events that occurred within the Executive Branch during the Trump Administration. They are not related directly to the UAP sections of the bill that am discussing here. However, it is conceivable that one or more of these broader whistleblower laws also could come into play in some future UAP-related scenario, depending on who has the pertinent information and other factors. The “authorized disclosure” process created by Section 1673 is a more streamlined and optimized process designed specifically for disclosure of UAP-related information to AARO and Congress.

Bill Sections 6802 and 6803:

General revisions pertaining to the Pentagon UAP office (AARO) and its operations, and AARO-conducted “historical record report” on government involvement in UAP

These sections, which are found on pages 2881-2903 of Rule Committee Print 117-70, make multiple changes in the groundbreaking UAP law that was enacted on December 27, 2021 (“Gillibrand-Rubio-Gallego”), 50 U.S. Code § 3373. Bill Sec. 6802 essentially writes over the entire 2021 enactment, preserving most of the original language but also making many changes. As I read it, the changes contained in this bill are enhancements and refinements, intended to further the purposes of the 2021 law. I do not see provisions diluting any key provision of the 2021 law.

This re-write originated in an amendment offered by Senator Roy Blunt (R-MO) at the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence (SSCI) closed-door voting session on June 22, 2022. (Again, those unfamiliar with the December 2021 law to which these changes are being made are advised to study my earlier articles of December 7, 2021 and July 14, 2022.)

Notably, the new bill significantly elevates the status of the AARO program by providing at Sec. 1683(b)(3)(A) that its director in general “shall report directly to the Deputy Secretary of Defense and the Principal Deputy Director of National Intellligence.” The Deputy Secretary of Defense is the second-ranking official in the vast Pentagon bureaucracy, sometimes referred to as the “alter ego” of the Secretary of Defense. This clause seems clearly intended to give AARO enhanced clout in its interactions with other components of the vast military bureaucracy.

The SSCI-approved bill (S. 4503) had contained a proposed definitional change to exclude from the scope of the phenomena being investigated “temporary nonattributed objects or those that are positive identified as man-made.” This language generated sharply conflicting interpretations among commentators over the past six months. Whatever it was intended to mean, it has been dropped from the final bill.

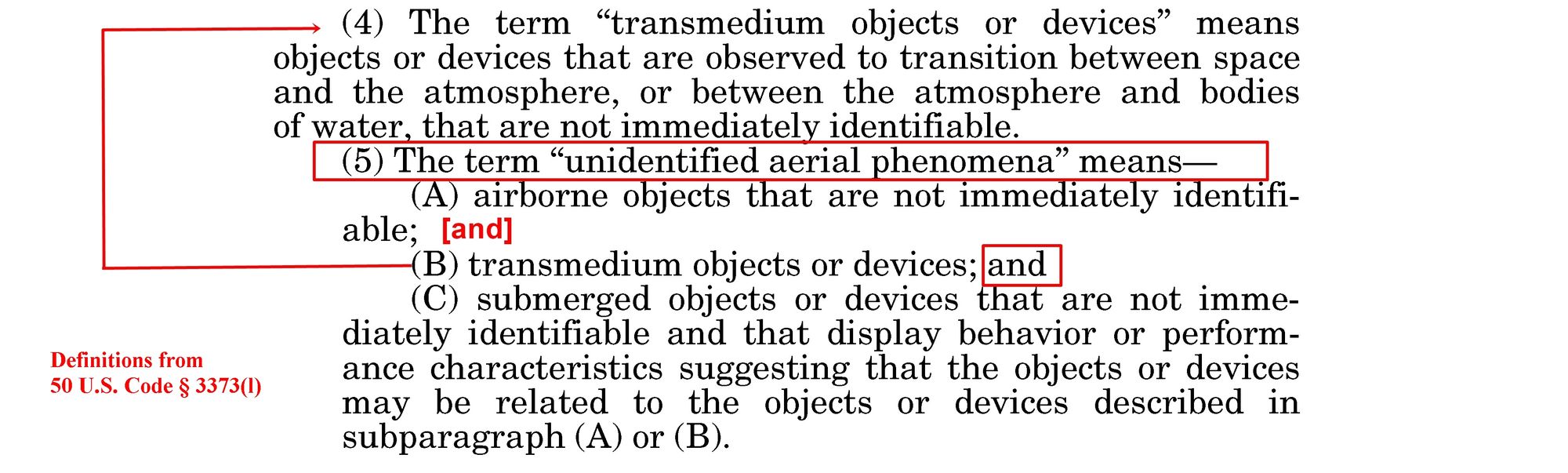

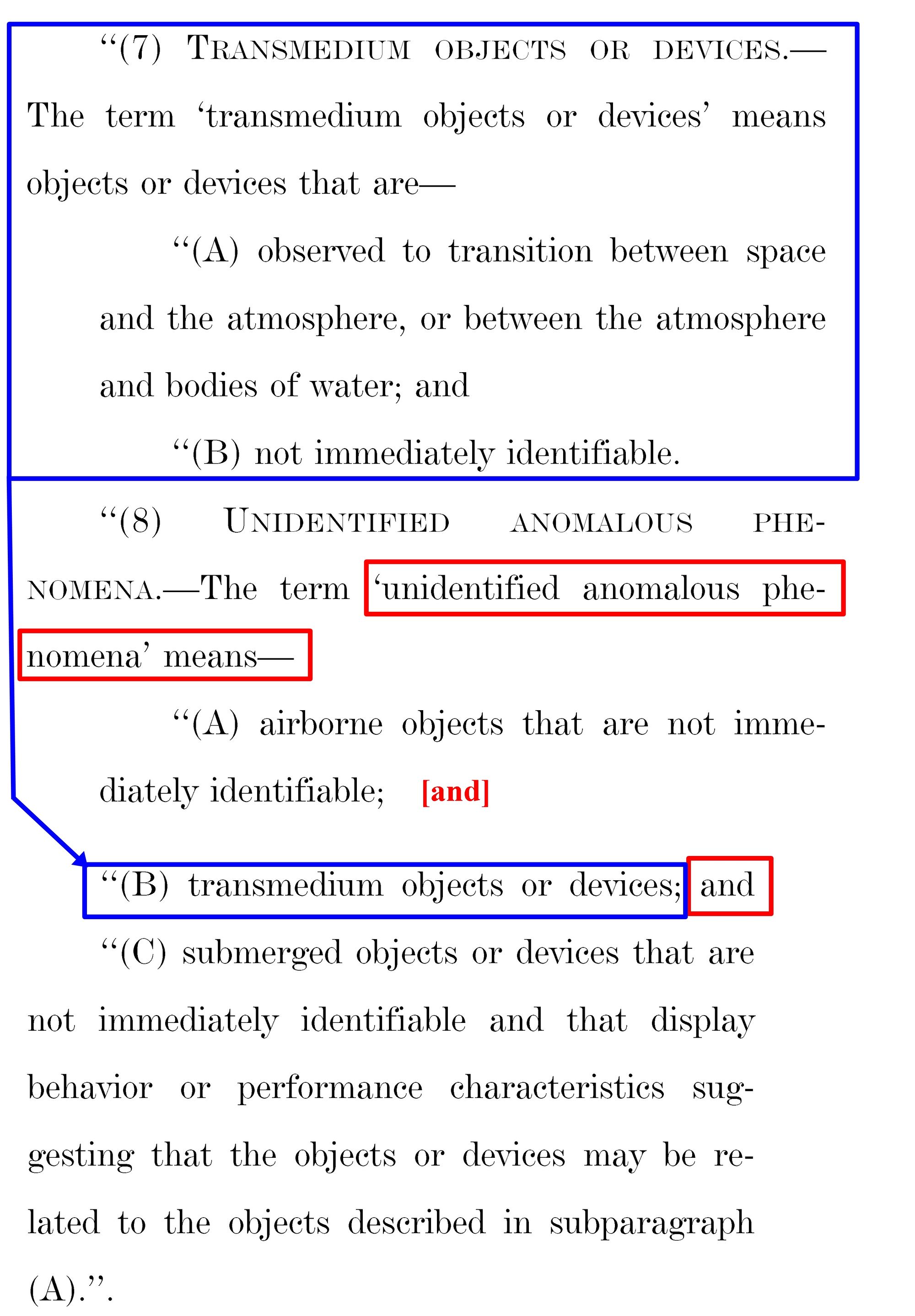

The bill does change the statutory catch-all term for the phenomena being targeted from “unidentified aerial phenomena” to “unidentified anomalous phenomena.” However, new term is defined in the same manner as old term was defined in the 2021 law, to include “(A) airborne objects that are not immediately identifiable; (B) transmedium objects or devices; and (C) submerged objects or devices that are not immediately identifiable and that display behavior or performance characteristics suggesting that the objects or devices may be related to the objects described in subparagraph (A).” The term “transmedium objects or devices” is again defined to mean those that are “observed to transition between space and the atmosphere and bodies of water” and “are not immediately identifiable.”

[Some commentators have jumped to the conclusion that the change from “aerial” to “anomalous” will vastly expand the scope of the phenomena that AARO would be tasked with investigating – to include, for example, “poltergeists” or “werewolves.” Such claims fail to take into account that the old term and the new term point to functionally identical definitions.]

The SSCI-reported bill mandated a historical study of involvement of the Intelligence Community in UAP matters, going back to January 1, 1947, by the Government Accountability Office (GAO), which is an arm of Congress. That proposal originated at the June 22, 2022 voting meeting of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, in a second amendment offered by Senator Roy Blunt (R-MO). A slightly altered version later was approved by the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence (HPSCI) in its version of the Intelligence Authorization Act (H.R. 8367), approved by HPSCI on June 20, 2022. That bill never reached the House floor.

In those two versions of the proposal as approved by the two intelligence committees, the mandate for the historical study was placed on the Government Accountability Office (GAO), which is an arm of Congress. In the new bill version, however, the responsibility for the historical study and ensuing report is placed with AARO, with the GAO to perform only a later “audit” and congressional briefing functions.

The scope of the “historical record report” has, if anything, been broadened, now to include “the historical record of the United States Government relating to unidentified anomalous phenomena…” going back to January 1, 1945. The report is to include “a compilation and itemization of the key historical record of the involvement of the intelligence community with unidentified anomalous phenomena, including (I) any program or activity that was protected by restricted access that has not been explicitly and clearly reported to Congress; (II) successful or unsuccessful efforts to identify and track unidentified anomalous phenomena; and (III) any efforts to obfuscate, manipulate public opinion, hide, or otherwise provide incorrect unclassified or classified information about unidentified anomalous phenomena or related activities.”

The findings of the study are to be presented by AARO to the congressional defense and intelligence committees, and top leadership, in about one and one-half years. It is not immediately clear to me, simply on reading the revised bill, how much of this report (if any) ultimately might be made public, but it seems clear enough that the investigation will have to delve into a good deal of classified material.

— Douglas Dean Johnson

(My gmail address is my full name. My Twitter handle is @ddeanjohnson)

SUBSTANTIVE REVISIONS TO THIS ARTICLE MADE AFTER INITIAL POSTING

- December 7, 2022, 8 AM EST. Addition of graphics from Joint Explanatory Statement on the bill (issued December 7, 2022) and from the report of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence on S. 4503, the FY 2023 Intelligence Authorization Act (Report 117-132, issued July 20, 2022). Various small edits for clarity.

- December 8, 2022, 10 AM EST. Expanded and clarified paragraphs dealing with the bill provisions dealing with use of the “secure method” for reporting UAP-related data to AARO/Congress, the appropriateness of the term “whistleblower,” etc. Added paragraph and graphics comparing current definition of “unidentified aerial phenomena” with proposed definition of “unidentified anomalous phenomena.” Added paragraph discussing elevation of the director of the All-domain Anomaly Resolution Office (AARO) to now report directly to the Deputy Secretary of Defense, the second-ranking official in the Department of Defense.

- December 8, 2022, 2 PM EST: Noted passage of NDAA (H.R. 7776) by the U.S. House of Representatives on a roll call vote of 350-80 on Thursday, December 8, 2022, at 1:39 PM EST.