Western Europeans fully integrated merpeople into their cultural, religious, artistic and imperialist mindset during the Renaissance (1450–1700). Cities like Venice, Genoa and London fostered thriving art scenes that overflowed with representations of mermaids and tritons, while Christians seemed to carve more merpeople into their cathedral walls every year. Writers, artists and explorers, meanwhile, labored in describing and illustrating these strange monstrosities, especially after the printing press restructured literature forever in the mid-15th century. Suddenly, one did not need a hand-drawn image or handwritten text to encounter merpeople in all their glory; anyone could simply pick up a machine-reproduced copy at their local printer.

At the same time as this culture of merpeople exploded at home, Western Europeans pushed into strange new lands. From Africa to the “Far East” to the “New World,” European explorers simultaneously expanded and shrank notions of space and time, producing detailed maps and narratives that allowed a Westerner to investigate the world from the comfort of his desk with more accuracy than ever before. And in these monumental travels, Europeans found merpeople in abundance.

One might wonder whether such obsession fueled, or was fueled by, Westerners’ push into unknown worlds in the 15th century. In many ways, this “chicken or egg” conundrum is critical, as two developments—local belief and far-off sightings—created a legitimized belief in merpeople during the Renaissance. It made sense to early modern Europeans that such creatures as mermaids and tritons would reside in the furthest, strangest and most “savage” corners of the globe. Europeans thus found merpeople in every new land they explored, thereby fueling the Christian Church’s centuries-old narrative surrounding these monstrosities, while also validating Westerners’ interest in them.

Europeans not only wanted to “see” merpeople at home and abroad—they expected to, even needed to. Early modern Europeans’ deep-seated acceptance of mermaids and tritons cannot be discounted in investigations of this ground-breaking era. As is still the case today, when humans presume the legitimacy of a belief, they often adjust their worldview to fit these supposed realities. This confidence, moreover, is contagious, as surrounding individuals also begin to believe in those same alleged truths. Perception, in short, is everything.

For laypeople, churchmen and philosophers alike, the “strange facts” of merpeople and other monstrosities not only confirmed, but also complicated, long-held assumptions about the Earth and humanity’s place in it. Monsters, in this framework, had as much to tell Westerners about themselves as they did the mysterious new worlds that they seemed to “discover” by the day.

Mermaids continued as mascots for the defamation of the feminine, representing religious traditions as well as folk-portents of storms, doom and death.

Yet, even with Europeans’ willingness to push the limits of their knowledge, long-held prejudices continued to color their analysis of the world around them. The denigration of the feminine in particular reared its ugly head in early modern Europeans’ worldviews. This, of course, was nothing new, as the Christian Church had spent the last ten centuries equating femininity with inferiority. Renaissance women accordingly experienced a fringe existence in public society. One Englishman opined that “hath no language [as English] so many proverbial invectives against women,” while another described women in simple, damning language: “you live here on earth as the world’s most imperfect creature: the scum of nature…the guardian of excrement, a monster in nature, an evil necessity, a multiple chimera.” Mermaids continued as mascots for the defamation of the feminine, representing religious traditions as well as folk-portents of storms, doom and death. Perhaps even more overtly, 16th-century Westerners often called prostitutes “mermaids” or “sirens.” Here was the ancient mermaid repurposed for modern ideologies, and she was not alone.

Europeans found all sorts of monstrous creatures in the Americas. Just as Marco Polo noted a variety of wondrous flora, fauna and creatures in his eastern travels, so too did New World explorers like Sir Walter Raleigh and Christopher Columbus claim to interact with everything from headless men to cyclops to the cynocephalus. Though hindsight relegates these creatures to fantasy, other animals proved very real and just as terrifying to early modern Europeans. The female opossum, for instance, was a strange New World “composite creature,” combining parts from Old World animals and humans to create “an inorganic multiplicity.” She especially exposed Europeans’ perception of the New World as a place that might hybridize their bodies and minds, thereby steadily transforming these supposedly civilized Old World people into vulgar, weakened reflections of their savage surroundings. In many ways, because of New World habitation, Europeans worried that they themselves might become monsters.

These climatic, environmental and biological fears coalesced around Europeans’ perceptions of merpeople. Western travelers expected to find mermaids and tritons in the oceans, rivers and lakes of the Americas. Europeans had, after all, already encountered merpeople off the coasts of their own nations; surely the distant, foreign, hybridized New World must boast even more of these monstrous creatures. Interacting with and understanding these beings might pull back the veil on the mysteries of the world and help Europeans to better understand mankind’s ever-evolving place in it. In a more practical sense, a deeper knowledge of merpeople might also allow Westerners to more effectively adapt to—not to mention conquer—the New World. As the English naturalist John Josselyn remarked after hearing an alarming tale of a merman encounter in Maine in 1638, “there are many stranger things in the world, than there are to be seen between London and the Stanes [present-day Staines].”

Before the 15th century, Europeans’ mermaid sightings were few and far between, and generally rested on ancient stories, bestiary descriptions and folklore. The 12th-century contacts in England and Holland proved most enduring, but still remained tethered to allegorical lessons or religious impulses. As Europeans pushed into strange new worlds filled with mysterious creatures, their interaction with merpeople skyrocketed, both at home and in the mysterious locales they visited. As already mentioned, it is impossible to know which influenced the other—were heightened interests at home driving sightings abroad, or were Europeans’ foreign interactions with merpeople leading them to find more of these strange hybrids in their own waters? These heightened 15th-century global interactions revealed much about Europeans’ evolving worldviews. Not only did Europeans’ relationships with mermaids and tritons steadily transcend mere religious lessons or folklore in the Renaissance Period, they also reflected Europeans’ visions of imperial might, natural plenty and philosophical wonder.

Here was the first European to visit the New World (as far as most 15th-century Western Europeans knew), and what was one of the first strange creatures he saw? A mermaid.

Any investigation of Western Europe’s 15th-century push into the Americas must begin with Christopher Columbus; doing so through the lens of merpeople is no exception. Upon arriving in the West Indies in 1493, the intrepid explorer claimed to see three mermaids splash out of the choppy waves surrounding his ship. While Columbus found mermaids “not so beautiful as they are painted,” he conceded that, “to some extent they have the form of a human face.” The importance of Columbus’s sighting cannot be underestimated. Here was the first European to visit the New World (as far as most 15th-century Western Europeans knew), and what was one of the first strange creatures he saw? A mermaid. Just as Columbus helped to create the perception in Europe of an “opened” or “discovered” New World, so too was he vital in the fabrication of Europeans’ beliefs that merpeople lived across the Atlantic Ocean. This was a strange land defined as much by “utopian visions of benign plenty” as “negative images of monstrosity.”

Interestingly, over the next hundred years Europeans’ sightings of merpeople occurred everywhere but the New World. Much of this probably boiled down to simple numbers. Before the 17th century, the English, French and Portuguese had little success in the Americas, as Spain ruled the seas with its vast armada protecting vessels riding low from loads of South American silver and gold. Other nations could not send as many men across the Atlantic, nor could they establish permanent settlements. Closer to home, however, Western Europeans began to thrive, as did their interactions with merpeople.

__________________________________

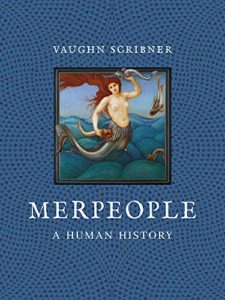

Reprinted with permission from Merpeople: A Human History by Vaughn Scribner, published by Reaktion Books Ltd. Copyright © 2020 by Vaughn Scribner. All rights reserved.