For a short time during the mid-1990s, a mysterious freshwater beast said to inhabit a lowland lake on the island of New Britain, east of New Guinea, was making waves in both the literal and the literary sense. Known mostly as the migo (but see later for a multitude of other monikers), it hit media headlines worldwide, featuring in numerous reports and articles globally, due to some very intriguing film footage that had lately been obtained by two Japanese expeditions, which was claimed to show this mystifying, unidentified creature swimming in Lake Dakataua.

But then, just as suddenly as it had raised its hitherto cryptic head above the water surface, the migo abruptly vanished from the news, never to be heard of again, except for a very occasional mention here and there in cryptozoological circles.

Consequently, it is high time, surely, to resurrect this long-forgotten mystery beast, reviewing its very convoluted, controversial history in the present two-part ShukerNature article. Indeed, as far as I am aware, this article constitutes the most extensive coverage of the migo published since the 1990s.

The migo first attracted notable attention beyond its island homeland on 1 February 1972, when a Japanese newspaper entitled the Mainichi Daily News reported a strange water monster known locally by this name, which supposedly inhabited Lake Dakataua, a caldera lake in the western portion of New Britain. At approximately 320 miles long, New Britain is the largest island in the Bismarck Archipelago, situated off the eastern coast of Papua New Guinea (PNG), which is the country occupying the eastern half of the island of New Guinea, and to whom the Bismarck Archipelago belongs. The lake has a diameter of 1400 ft, has a maximum depth of roughly 400 ft, and contains a submerged volcano plus three small islands.

According to Shohei Shirai, at that time the head of the Pacific Ocean Resources Research Institute, who was quoted in that newspaper report, the migo was similar in appearance to a mosasaur. This is the name given to a taxonomic superfamily of sometimes very large prehistoric lizards (the biggest species was up to 56 ft long) that were closely related to today’s monitor lizards or varanids. However, they were exclusively aquatic in lifestyle, equipped with flippers and a laterally-compressed tail, the latter being portrayed with a fin in some restorations. Other than Mosasaurus itself, the most famous and frequently depicted mosasaur was North America’s very impressive Tylosaurus, whose largest species is believed to have attained a total length of up to 46 ft.

Although mosasaurs are traditionally assumed to have been wholly marine in lifestyle, one exclusively freshwater species is now known – Pannoniasaurus inexpectatus, which was formally named and described in 2012 from fossilized remains found in what is today Hungary. According to the current fossil record, the mosasaurs had all become extinct by the end of the Cretaceous Period, around 66-65 million years ago, along with the last dinosaurs, plesiosaurs, and pterosaurs.

In January 1994 (not 1993, as sometimes erroneously claimed online), after arriving in PNG during the rainy season a crew from a Japanese TV production company named the Stream Company, and headed by Nadaka Tetsuo, journeyed on to New Britain and thence to Lake Dakataua in the hope of encountering the migo. Moreover, after setting up cameras around this lake, they actually succeeded in filming what they deemed to be its enigmatic denizen, which was duly included in a TV documentary programme subsequently screened on Japanese TV. Yet with the internet still in its infancy back then, so that sharing film footage, TV shows, etc, online was by no means a common occurrence, and with no excerpts from it shown on UK TV at that time either, it didn’t seem likely that I’d manage to view this programme.

Happily, however, fellow cryptozoologist Jon Downes of the CFZ had recently received a 1st-generation copy video of it from a Japanese correspondent, Tokuharu Takabayashi, and kindly prepared from it a 2nd-generation copy video that he then sent to me for my own personal viewing. Below is an abridged version of the lengthy descriptive account that I wrote after viewing the documentary.

After arriving at Lake Dakataua, the Japanese TV crew met the chief of a village near to the lake, and on the third day of their visit they interviewed some local eyewitnesses, sailed on the lake, and obtained footage of what they claimed to be the migo. They also attempted vainly to lure the migo using dead chickens, and lowered a cage and sound-recording equipment into the water, In addition, they sent divers into the lake and nearby sea, as it was suggested that the horseshoe-shaped Dakataua might be connected to the nearby sea via underwater channels.

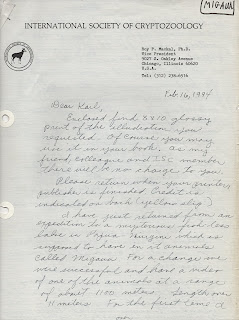

Comments were exchanged on-screen with Prof. Roy P. Mackal, an eminent Chicago University biologist with a longstanding interest in cryptozoology, who had accompanied the TV crew to Lake Dakataua and had served as the documentary’s scientific advisor. Roy had previously led various expeditions of his own in search of aquatic mystery beasts around the world, and he regularly corresponded with me via letters and telephone calls concerning a wide range of cryptozoological subjects.

Roy mentioned to me in one such letter that although he had advised against doing so, Shirai’s mooted mosasaur identity was promoted throughout the documentary by its makers. However, their cause was not assisted by a woefully inadequate computer-animated model with an inflexible body.

Excluding some footage of a blurred hump, what initially appeared to be the actual migo footage obtained by the Japanese TV crew consisted of two sections. The longer of these, lasting approximately 5 minutes and shot at a distance of about 1200 yards according to Roy, showed what Roy referred to in the documentary as three different body portions of a very long, large animal, travelling through the water from right to left across the screen. There was an indistinct head, staying out of the water throughout the footage, Behind this was a smaller portion that could have been a neck. Further back, maintaining a constant distance from the ‘neck’, was a large flattened hump that seemed to be propelling the ‘head’ and ‘neck’. Every few moments, the hump submerged, then swiftly bobbed back up, seeming to show that the creature was propelling itself via vertical undulations – a mode of progression normally exhibited by mammals, not by reptiles or fishes. There were some close-ups, which seemed to show that the dorsal surface of the hump was serrated, but this may have been an optical illusion.

Earlier in the documentary, there were a few seconds of footage that on first sight seemed much more impressive. When I forwarded it frame by frame, it revealed what appeared to be a section of the body rapidly emerging from the water in a vertical upsurge and bearing two slender projections resembling dorsal fins or spines, before submerging again – followed immediately by the vertical emergence of what may have been a tail, bearing two horizontal, whale-like flukes. Unfortunately, however, and as confessed very sincerely and apologetically by Jon himself, due to what he subsequently referred to as the extremely primitive nature of the only video-copying equipment that he had been able to access at that time the quality of the 2nd-generation copy video of the documentary that I had received from him was extremely poor (“somewhat akin in quality to one of the ‘bootleg’ copies of Disney movies which one can purchase at car boot sales” is how he subsequently described it). Jon also stated: “It appears that my equipment even managed to miss out bits of the documentary”.

Due to this lack of visual clarity and continuity, I had not realized that those above-noted few seconds of footage earlier in the documentary had apparently been filmed by the TV crew not at Lake Dakataua, but instead at sea while approaching New Britain in a boat, and actually showed some dolphins partially surfacing near to the boat. Happily, this was readily discernible in the better-quality 1st-generation copy video that Jon had received from Japan and I was swiftly informed accordingly, thereby saving me from wasting much time contemplating this particular section of footage.

Following his return in mid-February 1994 to the USA from New Britain, Roy corresponded with me in depth concerning the migo, via a series of letters beginning with one dated 16 February 1994 (and reproduced in full above for the very first time anywhere) that I have retained on file (and in which he always referred to it as it the migaua) as well as via a number of telephone conversations. He stated that it was about 33 ft long (an estimate that he subsequently revised upward to 50 ft – see later) and travelled at a speed of 4 knots.

Initially ruling out a crocodile or a fish identity, being influenced by its apparent locomotion via vertical undulations, he postulated that it was an evolved, surviving archaeocete. In other words, Roy was suggesting that the migo may be a member of a primitive taxonomic group of cetaceans (whales), the archaeocetes, but one that had not become extinct at least 25 million years ago as indicated by the current fossil record for these creatures, but had instead survived to the present day and in so doing had therefore undergone 25 million years or more of continued evolution, which may conceivably have rendered their bodies more flexible than those of their fossil antecedents.

Archaeocetes include the very elongate basilosaurids (aka zeuglodontines), such as the famously huge Basilosaurus, which officially died out just under 34 million years ago. One species, B. cetoides, is believed to have reached a total length of almost 70 ft. Basilosaurids may have been able to undulate vertically, although the current palaeontological consensus is that those known from the fossil record were far less capable of such movements than had traditionally been believed and depicted in early illustrations.

Judging from their dentition, basilosaurids were carnivorous (as opposed to planktonivorous, like certain very large present-day cetaceans). However, during an limnological investigation of Lake Dakataua during October-November 1974 (whose findings were published in February 1980 by the scientific journal Freshwater Biology), PNG-based wildlife biologists E.E. Ball and J. Glucksman discovered that its waters were very alkaline, and that although it contained an abundance of invertebrates in its upper levels, as well as amphibians, it did not contain any fishes. So if, in view of its seemingly elongated body, the migo is indeed a basilosaurid archaeocete, what does it feed upon?

As Roy disclosed, the answer is simple: namely, the abundance of waterfowl that settle upon the lake’s surface, their presence there also having been confirmed by Ball and Glucksman in their 1974 study. The need to remain near the surface in order to seize these birds presumably explains why the migo is seen more often (and filmed more easily!) than other supposed lake monsters, which seemingly feed predominantly upon fishes and therefore do not break the water surface so frequently.

According to the afore-mentioned Tokuharu Takabayashi, Lake Dakataua was visited in October 1978 by Japanese cryptozoologist Toshikazu Saitoh, who learned from natives in the nearby village of Blumuri that the lake monster was known to them variously as the massali, masalai, and mussali (all three names translating as ‘spirits’). It was first seen during the summer of 1971 by five eyewitnesses, who said that it was about 30 ft long, and had a relatively small head with long pointed jaws, like a crocodile’s, containing many sharp teeth; plus a long neck, a burly but streamlined body, a slender crocodilian tail, and two pairs of flippers (the front pair noticeably larger than the hind pair) that resembled those of a marine turtle.

The image conjured forth when all of these morphological features are combined actually recalls a mosasaur, as favoured by the Japanese team, rather than the basilosaurid identity favoured by Roy, especially as basilosaurids possessed only vestigial, scarcely-visible external hind limbs, their tail was not crocodilian, and their neck was not long. However, there is one further migo feature still to be mentioned here, which throws all attempts at identifying this mystery beast into total confusion. According to the five eyewitnesses from summer 1971 noted above, the creature that they saw was covered in short black hair!

Mosasaurs were true lizards and were covered in scales, as verified by several well-preserved fossil specimens. Even allowing for the effects of continued evolution, it is exceedingly unlikely that a modern-day mosasaur lineage would have evolved a hairy pelage. The same applies to a contemporary basilosaurid, whose streamlined body’s hydrodynamic efficiency would surely be impeded by a covering of hair.

Returning to the migo’s variety of local names, the usage of ‘massali’ and similar terms in preference to ‘migo’ by the Blumuri villagers could be dismissed as mere differences in dialect, were it not for the comments of yet another Japanese visitor to Lake Dakataua – namely, the explorer/writer Atsuo Tanaka, who stayed at Blumuri in September 1983. Confirming to Tokuharu Takabayashi that the villagers’ names for the lake’s monster were ‘massali’ and also ‘rui’, he asserted that ‘migo’ was actually the native name for a 3-ft-long species of monitor lizard! He also claimed that many of the villagers did not believe that anyone had seen a monster here, or even that it existed.

After personally observing some 6-10-ft-long crocodiles in Lake Dakataua, Atsuo Tanaka’s own opinion was that any ‘monster’ sightings that may have been made there were of a dugong or a crocodile (perhaps even an unknown species of the latter reptile, but more probably either the New Guinea crocodile Crocodylus novaeguineae or the larger saltwater aka Indopacific crocodile C. porosus).

Incidentally, a third identity proffered for the migo that just like a surviving mosasaur or a living archaeocete invoked a prehistoric survivor but which attracted far less public attention was inspired by a giant Mesozoic crocodilian related to today’s alligators. Formerly called Phobosuchus but nowadays known as Deinosuchus, it is currently represented by four fossil species, and an undiscovered modern-day descendant of this formidable reptile was suggested in relation to the migo by mystery investigators Edward Young and Ronald Rosenblatt in a short Fortean Times magazine article (December 1994/October 1995) reviewing cryptozoological creatures reported from, and recent mainstream zoological discoveries made in, New Guinea and its outlying islands.

Known from the fossil record to have existed 82-73 million years ago during the Upper Cretaceous, Deinosuchus is believed to have attained a truly monstrous total length of up to 40 ft (i.e. twice that of today’s largest known crocodilians). Consequently, in terms of size it may indeed match or come close to the lengths attributed to the migo.

Yet as with the mosasaur and, to a lesser extent, the archaeocete identities, the likelihood is not great that a modern-day Deinosuchus lineage exists not only undescribed by science but also unrepresented by any fossilized remains that even partially bridge the gap of many millions of years between itself and its most recent confirmed prehistoric precursors. In addition, Deinosuchus fossils are presently known only from North America, not from New Guinea or indeed anywhere else in the world.

Returning to Tanaka’s opinion that the migo sightings at Lake Dakataua may feature some form of recognised modern-day crocodile, such a situation if correct would be far from unprecedented – as revealed in Part 2 of this ShukerNature article (click here to access it), in which I explore in depth the fascinating crocodilian conundrum at the very heart of this truly monstrous mystery. Don’t miss it!