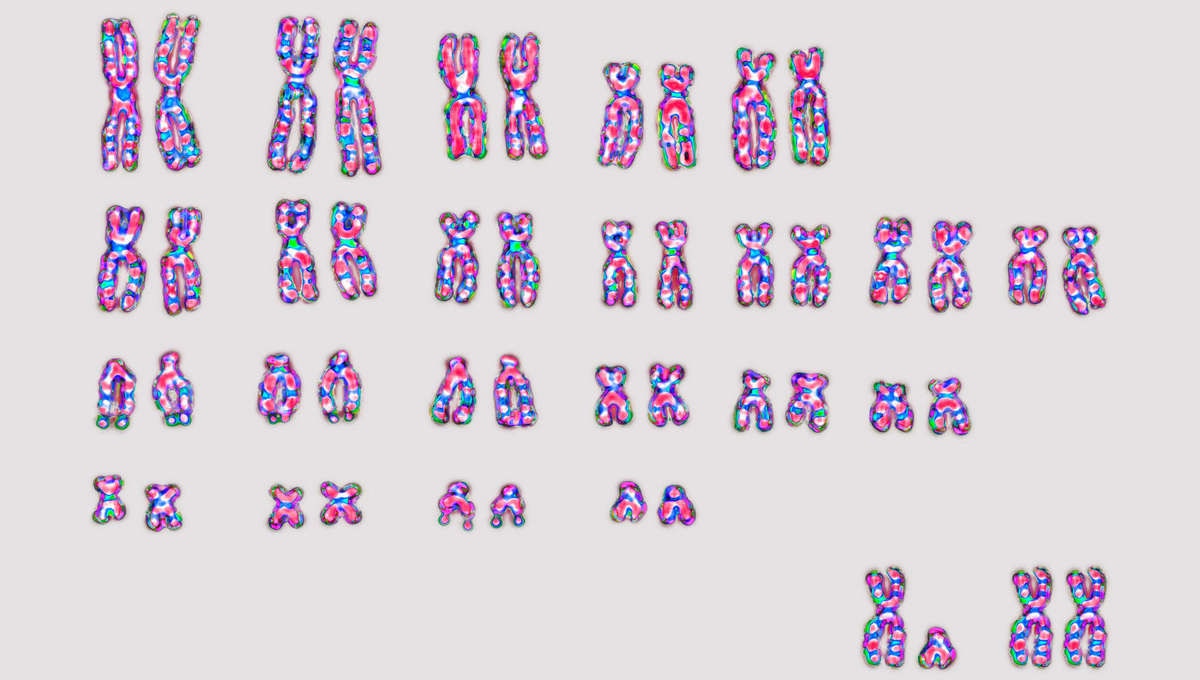

While dark matter might explain mystery mass in space, there is unknown matter right here on Earth—and it’s in our chromosomes.

Human chromosomes have now been found to be 20 times heavier than the DNA in them. Whatever is behind this extra weight could explain things which might reveal genetic mutations and anomalies that cause congenital diseases and damage to DNA that turns cells cancerous when they can no longer heal themselves. This is much more than the research team who discovered this, including physicist Ian Robinson of University College in London, ever imagined.

“It could be additional DNA not in the genome sequence, like satellite DNA. It could be a lot more proteins than those we know about,” Robinson told SYFY WIRE in an interview. “It could also be boring things like salt and water, but unlikely this much.”

What Robinson, who coauthored a study recently published in Chromosome Research, and his team have found out could be eventually contribute to the Human Genome Project, which revealed the mass of DNA molecules inside chromosomes. What had still not been resolved was the weight of the chromosomes themselves, which are so incredibly complex that many things about them continue to elude us. So how do you weigh something microscopic, with an equally microscopic weight, and get an idea of its total mass? X-rays.

X-ray ptychography does not technically weigh chromosomes. What it can do is create models that allow scientists to determining their mass, or at least come close, merging X-ray microscopy with more advanced coherent diffraction imaging (CDI). This causes X-ray beams to diffract, or spread out as they past through narrow spaces, and longer wavelengths of light (like infrared) are diffracted at less of an angle than shorter wavelengths (like UV). Zapping chromosomes with X-rays creates models that total mass can be determined from.

“Ptychography is usually a 2D method, and that’s how we used it,” Robinson said. “When the X-rays travel through the sample, they shift in phase by a measurable amount, and we used that amount to measure how many electrons are in each chromosome. That told us the mass.”

An entire set of chromosomes weighs 242 trillionths of a gram. That doesn’t sound heavy until you realize the weight of just the DNA in those chromosomes is drastically lower. Human DNA has 46 chromosomes in each strand, meaning 23 pairs in each cell, and a single strand is around six and a half feet long. It almost sounds impossible to cram into a cell. This is where proteins come in. If a genetically related function is needed, chances are there’s a protein for that, and specialized proteins compress DNA until it can fit inside a cell.

That all needs to be duplicated during mitosis, the kind of cell division that essentially clones cells. The chromosomes were imaged during metaphase in order to capture them at the right time to create the ptychographic model that would give away their weight. Metaphase is the third stage of mitosis in which DNA from the nucleus of the parent cell, which was duplicated before, is now separated into the two cells the parent is splitting into. That’s 3.5 billion pairs of DNA.

So many unknowns remain, from what this extra mass is to why there is so much of it to what it actually does for DNA, if it does anything. These questions will be plaguing scientists for a while.

“As to what insights on human DNA we could have when the identity of the mysterious extra weight is realized,” he said. “All I can say at this moment is that life is apparently more complicated than we know.”