The U.S. Senate may soon consider a far-reaching proposal to upgrade military and intelligence investigations of Unidentified Aerial Phenomena, and to require annual unclassified reports

by Douglas Dean Johnson

@ddeanjohnson on Twitter

WASHINGTON (Friday, Nov. 5, 2021, Noon EDT) — The U.S. Senate may soon consider a bold proposal to require the U.S. military and intelligence agencies to greatly increase the level of priority, coordination, and resources that they direct to the problem of unidentified aerial phenomena (UAP) — and to share at least part of what they know or learn annually with the American people.

The proposal was quietly filed on November 4, 2021, by Senator Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY) as a possible amendment to the Fiscal Year 2022 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA, H.R. 4350). The full U.S. Senate may take up that bill before the end of November.

The Gillibrand Amendment, if enacted, would continue and accelerate a process visibly begun in the 2019-2020 Congress under the leadership of Senator Marco Rubio (R-FL), who at that time chaired the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence (SSCI), and Senator Mark Warner (D-VA), who was then the vice-chairman of the SSCI, and who now chairs the committee.

Already in the current (2021-2022) Congress, three other UAP-related legislative proposals have been advanced, one of which has passed the House of Representatives. (I have previously reported on these, and I summarize them again below.) But the Gillibrand Amendment would go considerably further than the others in requiring the Department of Defense and the Intelligence Community to create new institutional arrangements and devote substantial resources to investigating and analyzing UAP, and to draw on UAP-related expertise from outside the government.

Also — very significantly and unlike the other three pending proposals– the Gillibrand Amendment would encourage progress towards greater UAP transparency by the government, by requiring issuance of public, unclassified reports on UAP annually, and by expanding the list of topics to be addressed in these reports to include several areas of particular interest to longtime students of the phenomena, including UAP events associated with nuclear weapons platforms.

It should be noted that senators have filed hundreds of possible amendments in anticipation of Senate floor action on the NDAA. Many of these will be withdrawn without a vote. Senator Gillibrand has so far made no public statement regarding her thinking regarding the UAP amendment or the underlying subject matter.

Still, to date only Senator Gillibrand has filed an full-blown alternative to the UAP language already approved by the House of Representatives – and Gillibrand’s proposal is markedly superior to the House language in multiple respects. If the Gillibrand proposal is embraced by other key senators — such as Senators Jack Reed (D-RI) and Mark Warner (D-VA), who chair respectively the Armed Services and Intelligence committees, and Senators Jim Inhofe (R-OK) and Marco Rubio (R-FL), the ranking Republicans on those respective committees– then it would have a good chance of becoming law.

Thus, it is possible that within the next couple of months, we could see Congress asserting itself to require serious, sustained, coordinated, and accountable UAP investigation by the Executive Branch — a historic development.

However, enactment of such a visionary proposal is far from a foregone conclusion. With UAP-related legislative proposals originating from multiple committees and lawmakers, and addressed to multiple national security agencies and officials, there is the risk that parochial interests, including even such factors as pride of authorship or jurisdictional concerns, could impede this proposal. Moreover, if history is any guide, it will not be surprising if some elements within the Executive Branch resist imposition of new UAP mandates and disclosure requirements.

WHAT HAS COME BEFORE

In mid-2020, the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence (SSCI) broke new ground by directing (in a public committee report on its Intelligence Authorization Act) the Director of National Intelligence (DNI) to issue a report on UAP, in both classified and unclassified form, six months after enactment of the bill. The bill was enacted in December 2020, activating the directive, which was fulfilled by the release by DNI Avril Haines on June 25, 2021, of a 9-page public report, “Preliminary Assessment: Unidentified Aerial Phenomena.” (Lawmakers on the congressional intelligence and armed services committees received a 17-page classified version of the report, as well as classified briefings.)

I will not recapitulate here the contents of the DNI’s public report, which have been widely covered and parsed. However, it seems safe to say that one result of the report has been to make discussion of UAP more respectable in the eyes of some scientists, journalists, and legislators, among others. For example, on August 6 the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA) held a forum on UAP – its first since the 1970s. In an essay that appeared in Scientific American on July 26, Harvard Astronomer Avi Loeb wrote, “The Pentagon report that was delivered to Congress on June 25, 2021 is intriguing enough to motivate scientific inquiry towards the goal of identifying its unidentified aerial phenomena (UAP),” and announced the launch of the privately funded Galileo Project, dedicated to searching for hard evidence of extraterrestrial technology.

Weeks after the DNI’s report was released, on August 4, the SSCI approved a new Intelligence Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2022 (S. 2610) that contained language directing the DNI and the Secretary of Defense to “require each element of the intelligence community and the Department of Defense with data relating to unidentified aerial phenomena to make such data available to the Unidentified Aerial Phenomena Task Force and to the National Air and Space Intelligence Center” (NASIC). (NASIC is a component of the U.S. Air Force.) As far as I can determine, this was the first time that a congressional committee had ever reported out a bill that proposed enactment of explicit, public-law mandates referring to unidentified aerial phenomena, unidentified flying objects, or any equivalent term.

Disappointingly, however, the SSCI language provided for no future unclassified public reports, opting instead to require quarterly classified updates for the armed services and intelligence committees of the House and Senate.

The House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence has included very similar language in its version of the IAA (H.R. 5412), although for some reason the House committee proposed the requirements as applicable only to the intelligence community and not to the Department of Defense. A press release issued under the authority of the chairman of the committee, Congressman Adam Schiff (D-CA), referred to the provision as “a bicameral provision mandating intelligence sharing with the Department of Defense’s UAP task force…[that] will ensure that the task force will be able to fully draw on all classified reporting about UAPs as they continue to investigate this mysterious threat to U.S. airspace and our military forces.”

The SSCI’s entire Intelligence Authorization Act, including its UAP provision, on November 4 was filed as a possible floor amendment to the NDAA – it is Senate Amendment 4461. (In some years, but not all, the entire Intelligence Authorization Act ends up being carried into law as an add-on to the NDAA.) However, to my mind the narrow UAP provisions contained in the House and Senate intelligence committee bills are now greatly overshadowed by the much more robust provisions found in the House-passed NDAA and, especially, in the Gillibrand Amendment.

HOUSE ARMED SERVICES COMMITTEE UPS THE ANTE

About a month after the DNI’s “Preliminary Assessment,” on August 30, the House Armed Services Committee upped the UAP ante when it unveiled its version of the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) (H.R. 4350), including 571-word section (Section 1652) dealing with UAP.

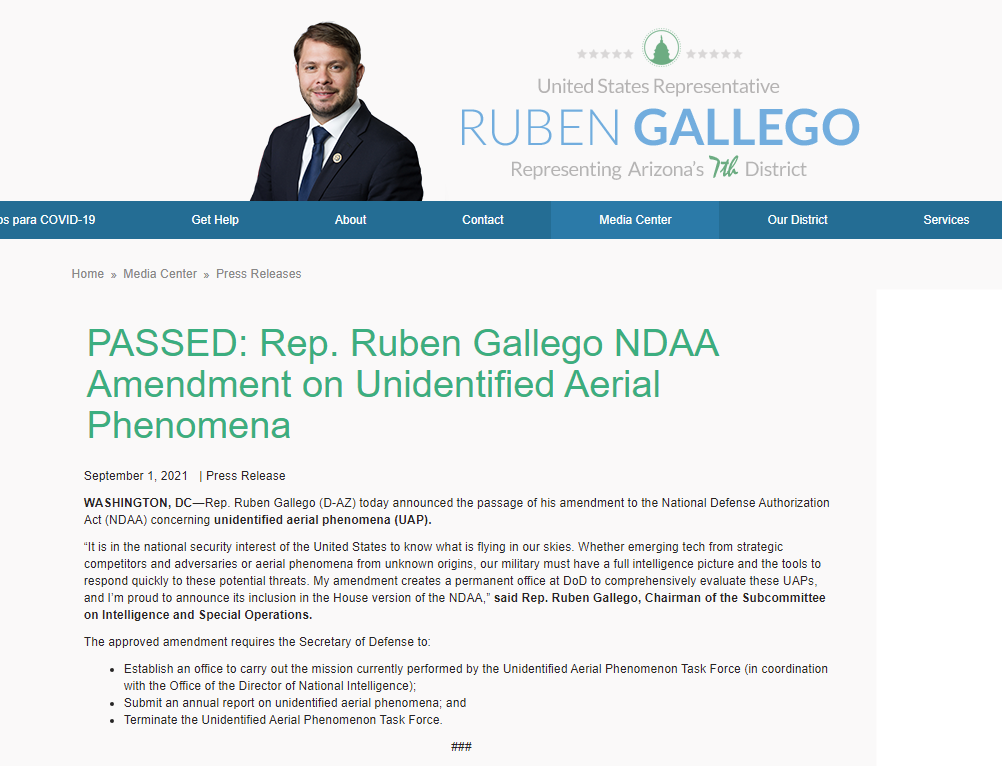

The UAP provision was initiated by Rep. Ruben Gallego (D-AZ), chairman of the House Armed Services Intelligence and Special Operations Subcommittee– a panel that had received a classified briefing from the UAP Task Force on June 17.

Gallego’s provision proposed UAP-related mandates to the Executive Branch that went well beyond anything previously proposed in public, and substantially stronger than the two Intelligence committee proposals. It would require the creation of a permanent UAP office within the office of the Secretary of Defense to replace the current UAP Task Force. It would also establish a list of seven specific “duties” of that entity, including to “synchronize and standardize the collection, reporting, and analysis of incidents regarding unidentified aerial phenomena across the Department of Defense,” “coordinating with other departments and agencies of the Federal Government,” and “coordinating with allies and partners of the United States, as appropriate, to better assess the nature and extent of unidentified aerial phenomena.”

In a press release issued September 1, the day the Armed Services Committee approved the bill, Gallego said, “It is in the national security interest of the United States to know what is flying in our skies. Whether emerging tech from strategic competitors or adversaries or aerial phenomena from unknown origins, our military must have a full intelligence picture and the tools to respond quickly to these potential threats.”

Members of the 435-member House of Representatives subsequently filed 860 possible amendments to H.R. 4650 (most of which were not made in order), but not one touched the UAP section. The bill passed on September 23 without any challenge whatever to the UAP language. This was the first time that either house of Congress had ever passed substantive legislation explicitly referring to “unidentified aerial phenomena” or UFOs by any other name.

Gallego, in an interview with POLITICO reporter Bryan Bender published September 25, expressed sharp dissatisfaction with the level of attention currently being given to UAP by the Pentagon.

“There’s been a total lack of focus across the national security apparatus to actually get at what’s happening here,” Gallego said. “I think there has been kind of a partial pastime of curiosity seekers that are within the Department of Defense but there has not been any professional initiative across the defense enterprise… so that we can actually make some deliberate and knowledgeable decisions.”

Gallego’s proposal, and its rapid and uncontested approval by the full House, engendered a measure of excitement among many elements of the diverse “ufological community,” but also some critiques. Many commentators, this writer included, expressed disappointment that the Gallego language (like the narrower proposals from the Senate and House intelligence committees) failed to require any future unclassified, public reports on UAP — raising the prospect that the DNI’s congressionally mandated June 2021 “Preliminary Assessment” would end up being a one-time teaser.

In a blog post published October 7, Christopher Mellon, who served as deputy assistant secretary of defense for intelligence during the Clinton and G.W. Bush administrations, commended Gallego “for recognizing the national security significance of UAP,” but added: “From even this brief assessment of next steps it should be clear that however well-intended, a small OSD [Office of the Secretary of Defense] UAP office lacking resources or authority is not the answer. Neither the UAP Task Force nor a small OSD office has the skill set and heft to effectively manage such a technically and bureaucratically complex undertaking. Indeed, a new OSD UAP office could have a pernicious effect if it led members of Congress to neglect the UAP issue afterward because they thought a small OSD office was sufficient to fix the UAP problem.”

Mellon added that a “number of powerful organizations need to be compelled to cooperate,” citing in particular historic and continued recalcitrance by the U.S. Air Force.

GILLIBRAND PROPOSES MUSCULAR UAP SCRUTINY AND CONTINUING DISCLOSURE

Senator Gillibrand appears to have taken the House-passed Gallego language as a starting point, but her proposal is much longer and more detailed. It is also much more assertive in creating a framework in which the government’s UAP-focused efforts would be placed under a robust central body, and armed with the explicit authorities and resources needed to begin to overcome bureaucratic and ideological resistance to robust UAP investigations. To my eye, it addresses a number of the defects that Christopher Mellon perceived in the Gallego language.

Senator Gillibrand has not previously been publicly vocal on the UAP issue. However, she serves simultaneously on both the Senate Armed Services Committee and the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, and these memberships have made her privy to classified briefings on UAP since 2017.

The Gillibrand Amendment would create a UAP-focused office (to be named the “Anomaly Surveillance and Resolution Office,” or ASRO) that would be placed “within an appropriate component of the Department of Defense, or within a joint organization of the Department of Defense and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence.” The head of the ASRO would be charged with “developing procedures to synchronize and standardize the collection, reporting, and analysis of incidents, including adverse physiological effects, regarding unidentified aerial phenomena across the Department and intelligence community.” In so doing, the ASRO head could “propose, as appropriate, the use of any resource, capability, asset, or process of the Department and the intelligence community.”

While the ASRO would be responsible for planning, coordination, and reporting, the amendment would explicitly require the Secretary of Defense and the DNI to designate existing “line organizations” (major military or intelligence components) “to conduct field investigations” of UAP, and to ensure that “the designated organization or organizations have available adequate personnel with requisite expertise, equipment, transportation, and other resources necessary to respond rapidly to incidents or patterns of observations” of UAP.

In addition, the proposal would require the ASRO head to develop “a science plan” to “develop and test, as practicable, scientific theories to account for characteristics and performance of unidentified aerial phenomena that exceed the known state of the art in science or technology, including in the areas of propulsion, aerodynamic control, signatures, structures, materials, sensors, countermeasures, weapons, electronics, and power generation, and to provide the foundation for potential future investments to replicate any such advanced characteristics and performance.” The amendment also requires the DNI and Secretary of Defense “to ensure that the designated line organizations have authority to draw on special expertise of persons outside the Federal government with appropriate security clearances.”

In apparent response to observations that government UAP investigations are currently hamstrung by lack of explicit, specific authorizations or appropriations for such activity in current law, the Gillibrand Amendment provides: “The obtaining and analysis of data relating to unidentified aerial phenomena is a legitimate use of funds authorized and appropriated to Department and elements of the intelligence community for (1) general intelligence gathering and intelligence analysis; (2) strategic defense, space defense, defense of controlled air space, defense of ground, air, or naval assets, and related purposes; and (3) any additional existing funding sources as may be so designated” by the Secretary of Defense or the DNI.

DISCLOSURE — MANDATE FOR FUTURE PUBLIC REPORTS

Beyond the provisions conferring institutional clout and resources on the UAP-investigatory enterprise, the Gillibrand proposal is markedly superior to both the House-passed Gallego language, and to the intelligence committee proposals, with respect to future sharing with the public of some part of what the government knows or learns about UAP.

Gillibrand’s language would mandate that the ASRO issue annual reports in both unclassified and classified form. While the reports would be transmitted to six designated congressional committees, and could include classified appendixes, the non-classified portions of the reports presumably would be made public. These reports would cover, at a minimum, 14 specific categories of information, ten of which were copied from the House-passed language, and four of which appear in the Gillibrand Amendment for the first time.

Among the mandated report components carried over from the House-passed bill are “the number of reported incidents of unidentified aerial phenomena over restricted air space,” an assessment of which UAP “can be attributed to one or more adversarial foreign governments,” “an update on the coordination by the United States with allies and partners on efforts to track, understand, and address” UAP, “an assessment of any health-related effects” of UAP encounters, and “an update on any efforts to capture or exploit” UAP.

To those House-approved provisions, the Gillibrand Amendment would add requirements that annual reports specifically address UAP incidents “associated with military nuclear assets, including strategic nuclear weapons and nuclear-powered ships and submarines,” incidents “associated with facilities or assets associated with the production, transportation, or storage of nuclear weapons or components thereof,” and reports “of unidentified aerial phenomena or drones of unknown origin associated with nuclear power generating stations [and] nuclear fuel storage sites…”

In addition to these detailed annual reports, the Gillibrand proposal would provide for twice-annual classified briefings to the House and Senate armed services and intelligence committees, which would include descriptions of newly reported UAP incidents.

Notably, the Gillibrand Amendment also requires that the chairs and ranking minority members of the armed services and intelligence committees be told, twice a year, “of any instances in which data related to unidentified aerial phenomena was denied to the [Anomaly Surveillance and Resolution] Office because of classification restrictions on that data or for any other reason.”

HOW ARE “UNIDENTIFIED AERIAL PHENOMENA” TO BE DEFINED?

One odd and glaring defect in the House-passed Gallego language was an absurdly constricted definition of “unidentified aerial phenomena.” Under the House bill, “UAP” was formally defined to mean only “airborne objects witnessed by a pilot or aircrew member that are not immediately identifiable.” Under that definition, a giant glowing disc entering the sea next to a surfaced submarine, or hovering over a Minuteman III silo, would not constitute “UAP.”

In contrast, the Gillibrand Amendment would define “unidentified aerial phenomena” broadly, as encompassing unidentified airborne objects, unidentified transmedium objects (“observed to transition between space and the atmosphere, or between the atmosphere and bodies of water”), and ”submerged objects or devices that are not immediately identifiable and that display behavior or performance characteristics suggesting that they may be related” to unidentified aerial or transmedium objects.

UAP ADVISORY COMMITTEE

The Gillibrand Amendment also contains a new section not found in any of the earlier three legislative proposals, requiring the Secretary of Defense and the Director of National Intelligence to establish an “Aerial and Transmedium Phenomena Advisory Committee” to advise the ASRO and the DNI on UAP-related matters.

The amendment provides for a maximum of 25 appointees, who must be able to pass muster “for a security clearance at the secret level or higher.” Of these, 20 would be persons designated by a variety of organizations named in the amendment– for example, two persons designated by the president of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, two persons designated by the Board of Directors of the Scientific Coalition for UAP Studies, and so forth. The Secretary of Defense and DNI would select five additional members.

The language seems intended to get a broad mix of expertise, seeking individuals who “possess scientific, medical, or technical expertise pertinent to some aspect of the investigation and analysis” of UAP, who have done research or writing that “demonstrates scientific, technological, or operational knowledge regarding aspects of the subject matter,” including “field investigations, forensic examination of particular cases, analysis of open source and classified information regarding domestic and foreign research and commentary, and historical information” on UAP.

The committee would have no policy-making power. But, by invitation of the DNI, Secretary of Defense, or the head of the ASRO, or on its own initiative, the committee could offer “advice regarding best practices with respect to the gathering and analysis of data on unidentified aerial phenomena in general, or commentary regarding specific incidents, cases, or classes of unidentified aerial phenomena.” In addition, the committee would submit an annual a report to the DNI, Secretary of Defense, and director of the ASRO, and the congressional armed services and intelligence committees, “summarizing its activities and recommendations.”

PROSPECTS

The annual National Defense Authorization Act is one of the few bills that Congress deals with each year that are considered “must pass.” Congress has enacted an NDAA in each of the past 60 consecutive years. However, the Senate shepherds of the bill — Senate Armed Services Committee Chairman Sen. Jack Reed (D-RI) and ranking Republican Jim Inhofe (R-OK)– face an especially challenging legislative environment this year. Although the bill is expected to reach the Senate floor later this month, it will do so during a period of intensive partisan conflict on multiple unrelated legislative issues, and severe time constraints.

Senate floor action will be followed by a House-Senate conference committee that will involve members of the armed services and intelligence committees of both houses, with UAP language only one of scores (if not hundreds) of issues in which incongruent language must be resolved, with a strong impetus to wrap up the bill before the end of the year.

Those who see great merit in the Gillibrand proposal should waste no time in conveying that view to their representatives in Congress. Such communications may be especially helpful if transmitted by constituents of lawmakers who sit on the Senate and House armed services and intelligence committees, who are listed below. The UAP-related language that finally makes it into law this year will be whatever is agreed on in House-Senate conference negotiations among members of those key panels – negotiations that occur mostly behind closed doors.

We live in a time in which there are few public policy issues of major consequence on which there are not sharp partisan divisions. So far, however, no such partisan split is evident with respect to UAP-related concerns. This may be a moment when it is possible for politically diverse lawmakers to act in determined concert, to create a statutory framework that will foster a coherent, well-resourced, and somewhat less opaque governmental posture towards the persistent and perplexing problem of unidentified aerial phenomena. Let’s do our best to not miss this opportunity.

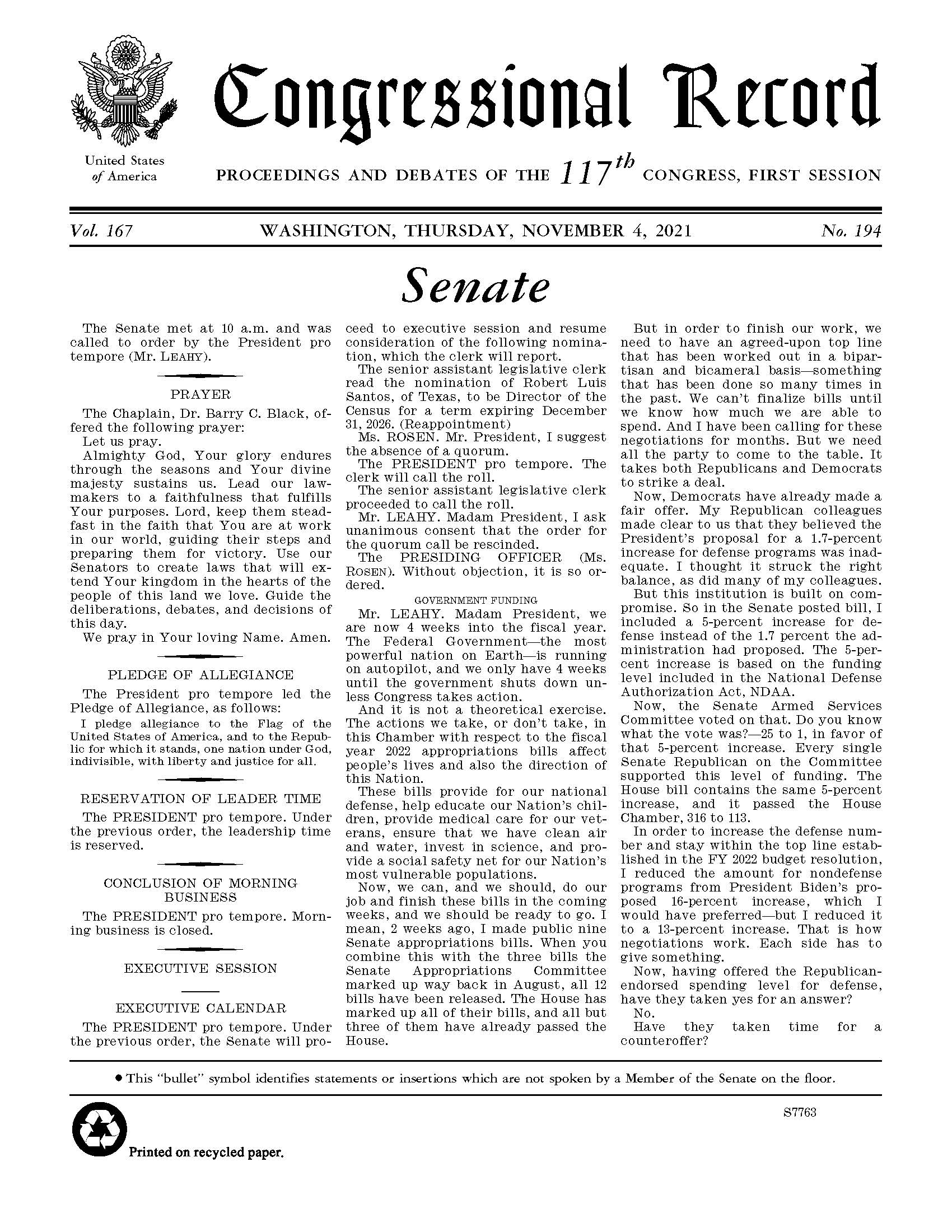

(The proposed Gillibrand Amendment to the National Defense Authorization appears on pages S7814-S7816 of the Congressional Record for November 4, 2021, as “SA [Senate Amendment] 4281,” as shown below.)

Opinions expressed on this blog are my own and not to be attributed to any other person, or to any organization, unless explicitly so stated. My gmail address is my full name, Douglas Dean Johnson, with periods on each side of my middle name. My Twitter handle is @ddeanjohnson

SENATE ARMED SERVICES COMMITTEE

DEMOCRATS

Jack Reed, Rhode Island, Chair

Jeanne Shaheen, New Hampshire

Kirsten Gillibrand, New York

Richard Blumenthal, Connecticut

Mazie Hirono, Hawaii

Tim Kaine, Virginia

Angus King, Maine

Elizabeth Warren, Massachusetts

Gary Peters, Michigan

Joe Manchin, West Virginia

Tammy Duckworth, Illinois

Jacky Rosen, Nevada

Mark Kelly, Arizona

REPUBLICANS

Jim Inhofe, Oklahoma, Ranking Member

Roger Wicker, Mississippi

Deb Fischer, Nebraska

Tom Cotton, Arkansas

Mike Rounds, South Dakota

Joni Ernst, Iowa

Thom Tillis, North Carolina

Dan Sullivan, Alaska

Kevin Cramer, North Dakota

Rick Scott, Florida

Marsha Blackburn, Tennessee

Josh Hawley, Missouri

Tommy Tuberville, Alabama

SENATE SELECT COMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE

DEMOCRATS

Mark Warner, Virginia, Chair

Dianne Feinstein, California

Ron Wyden, Oregon

Martin Heinrich, New Mexico

Angus King, Maine

Michael Bennet, Colorado

Bob Casey, Pennsylvania

Kirsten Gillibrand, New York

REPUBLICANS

Marco Rubio, Florida, Vice Chair

Richard Burr, North Carolina

Jim Risch, Idaho

Susan Collins, Maine

Roy Blunt, Missouri

Tom Cotton, Arkansas

John Cornyn, Texas

Ben Sasse, Nebraska

EX OFFICIO (non-voting) MEMBERS

Charles Schumer (D-NY), Senate Majority Leader

Mitch McConnell (R-KY), Senate Minority Leader

Jack Reed (D-RI)

Jim Inhofe (R-OK)

HOUSE ARMED SERVICES COMMITTEE

DEMOCRATS

Adam Smith, Washington, Chair

James R. Langevin, Rhode Island

Rick Larsen, Washington

Jim Cooper, Tennessee

Joe Courtney, Connecticut

John Garamendi, California

Jackie Speier, California

Donald Norcross, New Jersey

Ruben Gallego, Arizona

Seth Moulton, Massachusetts

Salud Carbajal, California

Anthony G. Brown, Maryland

Ro Khanna, California

William Keating, Massachusetts

Filemon Vela Jr., Texas

Andy Kim, New Jersey

Chrissy Houlahan, Pennsylvania

Jason Crow, Colorado

Elissa Slotkin, Michigan

Mikie Sherrill, New Jersey

Veronica Escobar, Texas

Jared Golden, Maine

Elaine Luria, Virginia, Vice Chair

Joseph Morelle, New York

Sara Jacobs, California

Kaiali’i Kahele, Hawaii

Marilyn Strickland, Washington

Marc Veasey, Texas

Jimmy Panetta, California

Stephanie Murphy, Florida

Steven Horsford, Nevada

REPUBLICANS

Mike Rogers, Alabama, Ranking Member

Joe Wilson, South Carolina

Mike Turner, Ohio

Doug Lamborn, Colorado

Robert Wittman, Virginia

Vicky Hartzler, Missouri

Austin Scott, Georgia

Mo Brooks, Alabama

Sam Graves, Missouri

Elise Stefanik, New York

Scott DesJarlais, Tennessee

Trent Kelly, Mississippi

Mike Gallagher, Wisconsin

Matt Gaetz, Florida

Don Bacon, Nebraska

Jim Banks, Indiana

Liz Cheney, Wyoming

Jack Bergman, Michigan

Michael Waltz, Florida

Mike Johnson, Louisiana

Mark E. Green, Tennessee

Stephanie Bice, Oklahoma

Scott Franklin, Florida

Lisa McClain, Michigan

Ronny Jackson, Texas

Jerry Carl, Alabama

Blake Moore, Utah

Pat Fallon, Texas

HOUSE PERMANENT SELECT COMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE

DEMOCRATS

Adam Schiff, California, Chair

Jim Himes, Connecticut

André Carson, Indiana

Jackie Speier, California

Mike Quigley, Illinois

Eric Swalwell, California

Joaquin Castro, Texas

Peter Welch, Vermont

Sean Patrick Maloney, New York

Val Demings, Florida

Raja Krishnamoorthi, Illinois

Jim Cooper, Tennessee

Jason Crow, Colorado

REPUBLICANS

Devin Nunes, California, Ranking Member

Mike Turner, Ohio

Brad Wenstrup, Ohio

Chris Stewart, Utah

Rick Crawford, Arkansas

Elise Stefanik, New York

Markwayne Mullin, Oklahoma

Trent Kelly, Mississippi

Darin LaHood, Illinois

Brian Fitzpatrick, Pennsylvania

EX-OFFICIO (non-voting) MEMBERS

Nancy Pelosi, California, Speaker of the House

Kevin McCarthy, California, Republican Leader