Down through the years, I’ve investigated

a number of mystifying animal artworks, depicting species before they were

officially discovered by science, or in locations far removed from where they

are officially known to exist. Examples from the former category include

various anachronistic representations of kangaroos (one of which I documented

in my book The Unexplained, 1996);

and the following case is a prime example (but one hitherto undocumented by me)

from the latter category. So I am greatly indebted to correspondent Cristian

Nahuel Rojas Mendoza for very kindly bringing it to my attention, on 17

December 2022, and which I lost no time in subsequently investigating – thanks, Cristian!

The work of art containing the portrayed out-of-place

animal in question is a magnificent yet surprisingly little-known pictorial encyclopaedia

in the form of a spectacular mural, entitled Quadro de Historia Natural, Civil y Geografica del Reyno del Peru (‘Painting

of the Natural, Civil and Geographical History of the Kingdom of Peru’), or QHNCGRP for convenience hereafter in this

present ShukerNature blog article of mine. Consisting of numerous miniature oil

paintings and accompanying text on a wood panel, it measures a very impressive 128

x 45.25 inches (325 x 115 cm).

QHNCGRP was authored by Basque-born

but (for three decades) Peru-based scholar José Ignacio Lequanda, who

commissioned French artist Louis Thiébaut to produce the paintings illustrating

it, and it was completed in Madrid in 1799 (click here

for an extensive article by Daniela Bleichmar documenting its history and

contents).

Today, this unique creation is held and

displayed at the Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales in Madrid, Spain (constituting

Spain’s national museum of natural history), which has produced an exquisite, lavishly-illustrated website devoted

specifically to it (click here to visit the

website). I strongly recommend that you access this site while reading my

article here, in order to appreciate fully the nature, context, content, and

visual beauty of this truly extraordinary, combined work of art and scholarship,

and in particular the two items from it under consideration here.

of QHNCGRP in its entirety – click to enlarge for viewing purposes (© Museo

Nacional de Ciencias Naturales – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair

Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Containing a grand total of 194 individual

images, QHNCGRP presents a picture-driven

history of the peoples, animals, and plants of Peru (or, in a few cases, Peru’s

South American environs). At its centre there is an annotated map of the

country, depicting, describing, and delineating its various administrative

divisions in different colours, as well as a picture of the mine

of Hualgayoc or Chota, emphasizing the significance of mining to Peru at that

time.

Constituting the outermost border or

frame of QHNCGRP is a series of 88

miniature paintings, each depicting a different Peruvian bird and plant, plus

four corner miniatures portraying Peruvian insects and reptiles. And running horizontally

directly below the uppermost edge of this ornithologically-themed border is a

row of 32 miniatures portraying various human forms, including indigenous

peoples and Western couples in various costumes.

Below these, and forming a second,

internal frame, is a series of numerous compartments containing Lequanda’s tiny

but voluminous handwritten text (he also added a descriptive label beneath each

animal miniature, and considerable text around the mine picture). Within this

second frame are not only four large and four smaller pictures depicting Peruvian aquatic animals but also (split into a left-hand block and a right-hand block of 30 each) a series of 60 miniature paintings, again depicting Peruvian animals. Well, 59 of them

are…

As for the 60th: This is the creature

portrayed in the miniature present at the right-hand end of the top row in the right-hand

block of 30 animal pictures. It seems to have been painted with especial

precision by Thiébaut in comparison with certain other of the animals portrayed

by him in QHNCGRP, and was labeled here

by Lequanda as a mountain-abounding ‘Dominican monkey’.

so-called ‘Dominican monkey’ miniature painting in close-up; and also shown (arrowed,

top row) in situ within QHNCGRP

– click to enlarge for viewing purposes (public domain)

In reality, however, as anyone even

remotely versed in mammalian identification will readily confirm, this

particular creature, its distinctive monochrome form being both instantly recognizable

and wholly unmistakable, is actually a black-and-white ruffed lemur Varecia variegata, the species depicted in

the photograph opening this ShukerNature article, and which is of course

endemic to Madagascar! No lemurs of any kind occur anywhere in the New World.

So why is there a portrait of a

Madagascan lemur in QHNCGRP, which is

exclusively devoted to Neotropical natural history and culture?

The most reasonable explanation, indicated

by Lequanda’s accompanying text (and also noted by Bleichmar in her afore-mentioned

article), stems from his great familiarity with the contents of Madrid’s

prestigious – and exceedingly prodigious – Royal Natural History Cabinet, which

was founded in 1771 and opened to the public in 1776. For within its collection

of zoological specimens was none other than a preserved example of the

black-and-white ruffed lemur. As this collection would have been consulted by

both Lequanda and Thiébaut during their joint preparation of QHNCGRP, one or both of them presumably

assumed mistakenly that the lemur specimen was of South American origin, and

thus its striking appearance was incorporated accordingly within QHNCGRP. But that is not all.

There is a second animal miniature in QHNCGRP that also attracted my interest

and attention when perusing the latter’s artworks. If you want to seek out this

picture in QHNCGRP, it’s the second

miniature along in the fourth row within the right-hand block of 30 animal

miniatures. Or, to make things simpler, here it is:

so-called ‘Nonga’ miniature painting in close-up; and also shown (arrowed, fourth row) in situ within QHNCGRP – click to enlarge for viewing purposes (public domain)

According to Lequanda’s accompanying

text, the Nonga lives on the banks of the River Huallaga (whose source is in central

Peru), and is a nocturnal creature greatly feared by the Indians, but which

according to Lequansda seems to be a forest spirit rather than a real entity.

When I first looked at this creature, I

thought straight away that it resembled a tree sloth in basic outward morphology.

But tree sloths do not stand upright, nor are they greatly feared by natives,

and far from being forest spirits they are very familiar members of the corporeal

animal community throughout the Neotropical zone.

However, their extinct relatives the ground

sloths did stand upright, might well be greatly feared by natives due to their very

large size and huge claws, especially if they happened to be ill-tempered

creatures, readily becoming aggressive if threatened, and, like many other belligerent

beasts, may indeed be deemed by their human neighbours to be supernatural

spirits as much as flesh-and-blood animals.

So could this miniature by Thiébaut be a

depiction of a modern-day, scientifically-undiscovered ground sloth? Certain South

American cryptids, such as the ellengassen and (especially) the mapinguary, are

already looked upon by some cryptozoologists and zoologists as potentially

constituting surviving ground sloths.

of a ground sloth (public domain)

Unfortunately for such romantic

speculation, however, the depicted creature’s tiny tail is much more comparable

with that of a three-toed tree sloth (two-toed tree sloths are tailless) than with

the fairly long and very sturdy caudal appendage exhibited by bona fide ground

sloths, which they used for support and balance when squatting upright.

Consequently, my personal opinion is that

this mystifying miniature painting was based upon a preserved three-toed tree

sloth, but whose normal behaviour of hanging upside-down from tree branches was

not known to Liébaut, so he portrayed it incorrectly as a bipedal beast

instead, thereby inadvertently recalling its officially extinct terrestrial

relatives.

Nor are a misplaced Madagascan lemur and a suspect sloth of the terrestrial variety the only zoological oddities to be found in QHNCGRP – click here for a continuation of this investigation, in which I reveal all manner of additional animals of the decidedly anomalous kind lurking incognito within its miniature masterpieces!

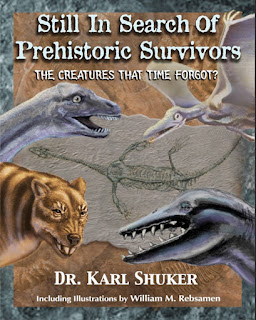

Nahuel Rojas Mendoza for alerting me to QHNCGRP

and, in so doing, adding another very intriguing zoogeographical anomaly from the

art world to my archive of such examples. For an extremely extensive account of putative

living ground sloths, be sure to check out my book Still In Search

Of Prehistoric Survivors.