Scientists have discovered a trove of nearly 600 obsidian hand-axes that were crafted more than 1.2 million years ago in Ethiopia by an unknown group of hominins, the family consisting of modern humans and our many extinct relatives, reports a new study.

The discovery pushes the timeline of obsidian tool use back by an astonishing 500,000 years, and reveals that the hominins who lived in this part of Ethiopia, known as Melka Kunture, must have been considerably skilled crafters in order to work with this capricious material.

Obsidian is a volcanic glass that forms from rapidly cooled lava, an origin that gives this rock its typical dark color and brittle structure. As a fragile and sharp-edged glass, obsidian is a useful material for making tools and weapons, but those same qualities make it tricky to sculpt because it can so easily break and cause injuries.

Many human cultures have relied on obsidian for both aesthetic and functional items over the past several millennia. However, the use of this glass deeper in the Pleistocene era, a period that spans roughly 2,580,000 to 11,700 is less common, with notable exceptions such as obsidian hand-axes found in Kenya that date back some 700,000 years.

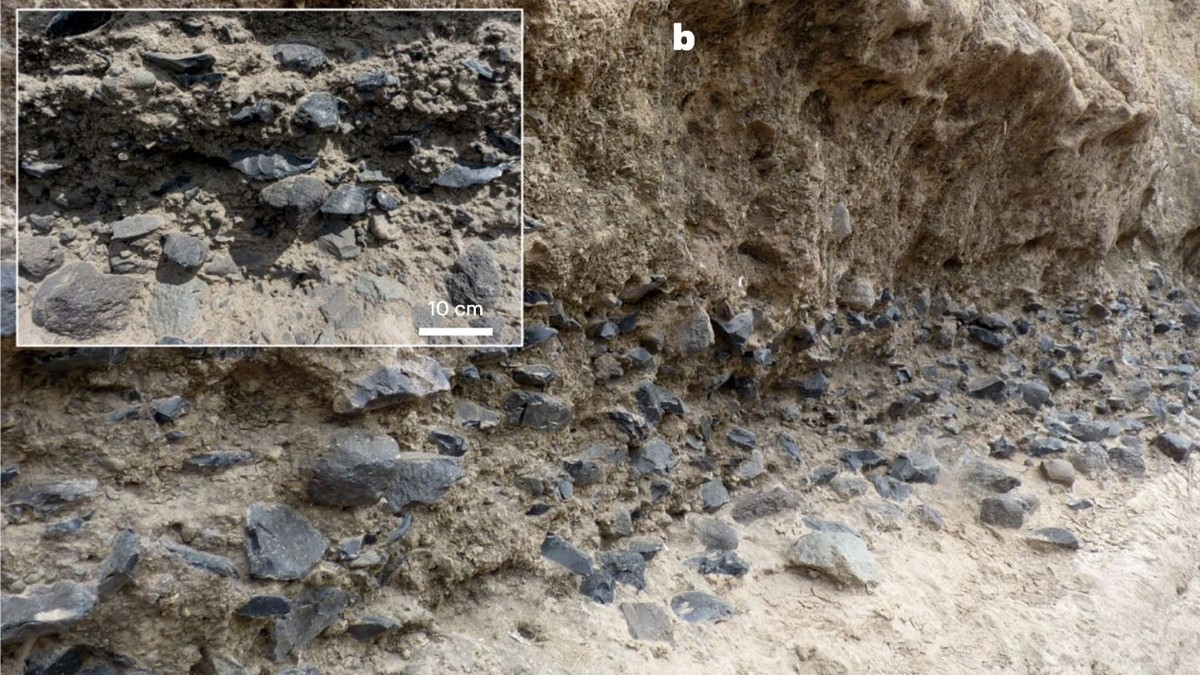

Now, scientists led by Margherita Mussi, an archaeologist at the University of Sapienza, have discovered what they call a “surge in obsidian exploitation more than 1.2 million years ago” by hominins living along Ethiopia’s Awash River, according to a new study published in Nature Ecology & Evolution. Indeed, of the 578 hand-axes the researchers found at Melka Kunture, all but three were made of obsidian.

“Following the deposition of an accumulation of obsidian cobbles by a meandering river, hominins began to exploit these in new ways, producing large tools with sharp cutting edges,” Mussi and her colleagues said in the study.

“We argue that…hominins were doing much more than simply reacting to environmental changes; they were taking advantage of new opportunities, and developing new techniques and new skills according to them,” the team added.

Humans are the only hominins that still walk the Earth today, but our wider ancestral family once included a variety of close relatives during the Pleistocene era. Some of these bygone hominins were sculpting simple stone tools as early as 3.3 million years ago, but the use of dedicated “workshops” for tool-crafting was previously assumed to have emerged much later in the archeological record.

“Pleistocene archaeology records the changing behavior and capacities of early hominins,” Mussi’s team noted. “These behavioral changes, for example, to stone tools, are commonly linked to environmental constraints.”

“It has been argued that, in earlier times, multiple activities of everyday life were all uniformly conducted at the same spot,” the researchers said. “The separation of focused activities across different localities, which indicates a degree of planning, according to this mindset characterizes later hominins since only 500,000 years ago.”

The hominins who lived at Melka Kunture now appear to have shattered that record, as the archaeological evidence suggests that they crafted their obsidian hand-axes with “remarkable” standardization and attention to detail that was “focused on the final regularization of the artifacts,” according to the study.

“We show through statistical analysis that this was a focused activity, that very standardized hand-axes were produced, and that this was a stone-tool workshop,” the team concluded.

The new study opens a tantalizing window into the mysterious hominin community that lived in this river ecosystem 1.2 million years ago, and learned to take advantage of some of the most challenging resources in its environment. Future discoveries may further expose the extent to which our long-lost relatives developed the adaptations that would ultimately help our own species gain a competitive edge in a beautiful, but dangerous, world.